Beteljuice and brainfever

At the Thai–Burmese border I was even less sure than usual what to expect on the other side. Burma, or Myanmar as it was renamed by the military junta that seized power in 1989, only opened up as a viable trans-Asia route three years ago. After an incredibly dark period cut off from the rest of the world, in 2015 Burma held its first democratic election since 1990. Much of the country is still off-limits to foreigners and camping wild is strictly prohibited. The first intrepid cyclists to transit the country reported being tailed by police on motorcycle day after day to prevent their pitching a tent or staying in unlicensed hotels, and to generally keep tabs on these new interlopers. One of the legacies of the totalitarian years is a culture of fear of running afoul of the authorities. Local people, afraid of official reprisals, will more than likely inform the police about a foreigner in their village or cornfield. Lots to think about. Only one way to find out though…

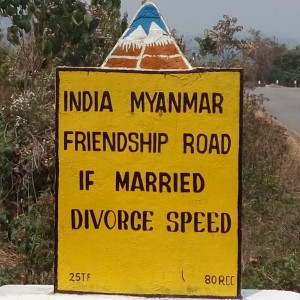

Crossing the border was a straightforward affair, apart from the frankly nuts set up for switching to driving on the right-hand side of the road in the middle of the Friendship Bridge – dodge the swerving lorries! Good-natured immigration police were impressed rather than suspicious of me travelling by bicycle and my early interactions with Burmese people were characterised by toothy smiles, gentle curiosity and helpfulness. As the afternoon wore on I passed through three or four more police roadblocks; still within 100km of the border there were far too many police around to make camping a sensible choice for my first night’s lodging. As I pondered the possibilities, I saw a few hundred metres away from the road the arresting spectacle of soft evening sunlight illuminating the graceful, golden funnel of a pagoda (Buddhist temple).

Although strictly as illegal as wild camping, staying in temples and monasteries is often the safest option for cycle tourers in Burma. Monks owe no loyalty to the military junta, and fearing no earthly retribution they are unlikely to turn you in, so the theory goes. My first tentative approach toward the temple was met immediately with smiles and receptive gestures from a lad who was tending the grounds, the monks themselves almost oblivious to my presence. I was offered a place to wash and then taken to a nearby restaurant where I got my first taste of Burmese cuisine and generosity – an array of delicious vegetarian dishes for which the bill had been paid in advance. After an early night sleeping under a scaled-up cake fly net on the deck of the schoolroom, I was all set for my first full day of cycling in Burma. But not until I’d eaten two sizeable breakfasts, first with the workers then with the nuns and lay members of this wonderfully generous community who anticipated my every need; I never had to ask for anything the whole time I was there.

Time was once more of the essence. My 29-day visa was just sufficient to get the Indian border with maybe one scenic detour via Bagan, once I obtained a visa for India in Yangon, the main city and former capital. Within a day or two the fast, horn-honking, close-passing traffic on the narrow, dusty arterial road to Yangon was starting to get to me. At the same time my long-suffering Salewa ‘5 continents’ shorts finally disintegrated. I seized on the synchronicity and rigged the ragged shorts as a warning flag on a piece of bamboo sticking out sideways from my pannier. Now enjoying a slightly wider berth from the crazy right-hand drivers, I still had to dodge the sticky red spit ejected from the windows of each passing bus, as drivers and passengers alike chewed incessantly on betelnut. Three long days and two late wild camps well-hidden in rubber plantations got me to the outskirts of Yangon at dusk. Like most cities in Asia, Yangon is not widely street-lit; my front light cut like a searchlight through the dust and smoke. Unlike in Hanoi a few months before, Yangon traffic is exclusively four-wheeled. A government decree excludes motorcycles and bicycles from the city, ostensibly for safety reasons, but I was never challenged as I weaved through the gridlock, the frustrated drivers forbidden from using their horns anyway. At 8pm, after 160 dusty kilometres, I staggered into a hostel I’d heard good things about and grabbed the last available bed, for once in the quietest corner of the building.

My first order of business in town was at the Indian embassy. I had half-killed myself to reach Yangon in time for a 72-hour visa turnaround and be on the move again before the weekend. Preliminary research warned that this office took miserly bureaucracy to the next level, and I noted carefully all the hoops I would be required to jump through. But Yangon’s weak and intermittent wi-fi network made the online application process a hair-tearing experience, and by the time I had my forms printed I was turned away on the grounds that the embassy processes only eight applications per day. That’s right eight, not eight-zero, just eight. FFS. Laying siege next day, I was second in line. But my hopes took another body-blow as my scanned photo was deemed incorrect and I was sent away to redo it and only re-admitted to the building after strenuous pleading. Then many US dollar bills were rejected – Burmese banks will accept only mint condition notes from anyone, foreign embassies included. The slimy assistant consul repeatedly tried to get a rise out of me, suggesting I put the slightly creased bills in an envelope to Barrack Obama and tell him we don’t want his money here; later that I should ‘love my queen’ when I answered his enquiries after her health with ‘what do I care’. To my immense relief my application and grossly inflated fee was eventually accepted on my fourth visit to the counter (164USD for UK citizens, $42 for EU and most other nationalities, reciprocating British immigration policy towards Indian nationals). But I now had a long unscheduled wait on my hands.

As I soon found out, there are worse places to spend a week than Yangon in February 2016. Optimism was in the air; last year the country successfully elected its first non-military president since the early 1960s and Aung San Suu Kyi was about to be made effectively prime minister. Amongst young people in particular there was a sense that the long hoped for change and opening up to the outside world was finally happening. Far and wide I ranged, wandering the side-streets of this colourful city, sampling the fantastic veggie street-food and cafes. Often I was the only westerner in the neighbourhood amidst the longyi-clad, tiffin-toting locals, but I seldom drew a second glance, and if I did it was always accompanied by a broad, welcoming smile. Perhaps slightly too relaxed one afternoon I accidentally-on-purpose ducked the entrance fee to the magnificent Shwedagon pagoda. Honestly it was more by luck than design that I found myself inside the central courtyard, chatting with monks and taking photographs in the evening light. After an hour sitting reading, minding my own business, a hawk-eyed young ‘helper’ spotted that I alone amongst the foreign tourists did not display an admission sticker and challenged me for my credentials. ‘Wait here’, says he. ‘Oh shit’, thinks I, sensing the long, muscular arm of Burmese security about to close around me. In a flash I slipped out the back the same way as I came in, not turning to answer calls of ‘excuse me, sir!’ as I shot barefoot down the 200m staircase to recover my sandals on the way out. You may think it pretty stupid to pick a country notorious for false imprisonment for a spot of recreational law-breaking – particularly without any shoes on – and you’d be right. But what is a boy to do for fun off the bike?

A week later I was all set to leave Yangon, replete with happy memories of writing in my home from home among the wonderful staff of Lil Yangon hostel; hanging out with Chris, a young entrepreneurial Burmese from Mandalay (and fellow Jonathan Livingstone Seagull aficionado); and with genial Germans Laura and Simon argued about Herman Hesse and practised the peculiar kissy-kiss sound used to call for waiters’ attention in South Asia, with hilarious results. Fun and games over, my first day out of Yangon would inevitably drop me near the town of Bago, where poor Carlos Perez had been violently attacked while cycle camping last year. Preferring to take no chances here, I sought a temple well away from the main road into town. At first all was well; various lay members of the community plied me with tea and biscuits, and showed me to a place to pitch my tent. Just as I was about to turn in for the night, a casually dressed young man approached by torchlight asking to see my passport. In the middle of brushing my teeth, I waved him away thinking him to be another of the curious young men who had hung around for an hour or so after my arrival. But he wouldn’t let it go, and I almost choked on my toothpaste when he said he was in fact the local policeman and that the people here didn’t understand the law about hosting foreigners. In the light of the dining area I could see he was smiling in a friendly way, his face painted pale yellow with thanaka paste. Once I produced my documents he affably offered me a cigarette and asked about my trip. It turned out that he was the nephew of one of the old guys at the temple, who was concerned that an unregistered foreigner could attract trouble for them, so had phoned his police relative for advice. In the end all he wanted was to write down my name and nationality on a scrap of paper and organise one of the youths to bring me some bananas for breakfast!

I liked Burma more and more. Next day I pushed north, running the gauntlet of betel juice-spit from buses that disgorged heedless passengers into the middle of the road, the rolling-stock unconverted from the days before the junta broke with colonial tradition and switched the country over to driving on the right. Collections for local temples lined the streets, blaring a cacophonous kind of DJ blether from maxed-out loudspeakers, often in competition with more shouting chuggers and distorted music a hundred yards further down the road. I grimaced through the noise, dust and fumes, tracking across the flat arable land that stretches for hundreds of kilometres between Yangon and the modern capital Nyapyidaw. Cover for camping was non-existent here and the land was alive with people. Reaching Kyauktaka at dark I tried my luck first at the Hindu temple (bafflement), then the neighbouring Buddhist temple (young monks sympathetic, surly abbot having none of it) and then the seedy, solitary guesthouse in town that a young lad from the Buddhist temple took me to (half an hour wasted while they stared at my passport, shouted at each other up and down the stairs then eventually claimed to be full). Okay, plan D then: go to the local police station and ‘make myself their problem’, a tactic recommended by other cyclists. But no one could direct me to a police station, most people who I asked making the dismissive ‘jazz-hand’ gesture beside their head that means ‘no, we don’t have that’. Tired, hungry and dejected I skulked out of town, resigned to bedding down in some mosquito infested field, probably in plain view. At the outskirts I passed a fire station and took a final throw of the dice, approaching the rag-tag crew kicking about in the front yard. One of them spoke excellent English, quickly cottoned on to my predicament and said they’d be delighted for me to stay with them, so long as the local busies agreed. Walking my bike down the street accompanied by my posse of ten firemen and interpreter, suddenly things were looking up.

The optimistic mood lasted all of ten minutes once inside the police station, i.e. until the local immigration officer arrived. A thoroughly unpleasant toad of a man, with mean, droopy eyes and a slack mouth wet with dark red dribble, and he was not happy about being called out to do his job in the middle of a nice betelnut binge. Phone calls were made, much was said between police and immigration officers – neither of whom spoke English – and it became obvious that I wasn’t going to be allowed to stay in the fire station. The fire crew were sent packing, and I was left in the sparse room under the glare of a single shadeless bulb, moths wheeling about dementedly, and I wondered where this was going. A local school teacher was fetched to interpret, although his English wasn’t half as good as the fireman, telling me that I had to cycle back the way I came for 34km to the nearest town with a tourist hotel. I had suffered stomach cramps and worse all afternoon, so I didn’t have to act to convey exhaustion at this point, and I made it plain that another two or three hours cycling in the dark on this treacherous road was out of the question, so I had better stay here. ‘It is not convenient for you to stay here’, the teacher kept saying, and talk turned to putting me on a bus back down the road. I parried that going south by any means would probably cause me to overstay my visa what about to the north? (These guys had no clue how long it takes to cycle 34km, originally suggesting it would take me less than an hour by loaded bicycle, so I felt quite at liberty to exaggerate).

So 48km north to a hotel in Phyu I was sent. A truck was produced and I was ushered into the back ‘to take care of my bike’. I didn’t twig what that meant until, as the engine started, three drunk young Burmese guys jumped in the back with me. I humoured their initial mischief and curiosity, but as the hour long journey wore on so did their increasingly obnoxious attempts to mess with my bike and get my attention by grabbing at me. I sensed that things were turning nasty and decided that it was inevitable that I was going to ‘lose my shit’ sooner or later, so it may as well be sooner. The next time the most irritating drunken monkey made a grab for my chest I caught and held his wrist, yelling that I do not like being touched and leave my effing bike alone. In retrospect, this was perhaps reckless bravado in a lonely place in a strange land, outnumbered three to one by heedless morons. But my bluff did the job, and I was unmolested for the rest of the ride. As we came into the town of Phyu the toe-rags became agitated again, but now they wanted me to join them to visit prostitutes, the whole night for 3000 kyat (less than 3USD). Too grim for words. Glad to be free from this mobile zoo cage, but saddened by the fate of whichever unfortunates were destined to take their money tonight, I checked into the motel at 10pm, hit the just-closing neighbouring restaurant for a beer and a tealeaf salad and collapsed into unconsciousness.

On balance, things could have gone worse. Other cyclists who had been bussed out of restricted areas had been compelled to pay for the privilege. I was not asked for money – I would have refused to pay anyway for such a trial – and I had not lost any ground in my journey north. But it was not an experience I cared to repeat, so I would not be giving myself up willingly to the tender mercies of the local police again. That night I did my well-rehearsed mime act at a temple well away from any major towns and received the customary too-generous-for-words reception.

Near Swar I left the main road and cut into the low scrappy hills that separate the Sittang and Irrawaddy valleys. People’s demeanour changed abruptly. Many locals seemed utterly nonplussed by my presence, affronted almost. I was getting more blank stares than smiles. Others were completely stoned out of their gourds, staggering in the road almost under my wheels, walleyed in opium stupors. A badged but non-uniform policeman stood over me as I ate lunch, leering menacingly and fidgeting with his rifle, eventually placated by my pointing in the direction of Bagan. Lots of people were cordial and curious as usual, but there was a weird vibe in this region that set me on edge. I later discovered that this cross-country road is in fact off-limits to foreigners. These hills also marked the start of the once mighty teak forests of central and northern Burma. Decades of over-extraction throughout the colonial period and since have for the most part reduced the forest to a scrubby, straggling mess of charred and still burning softwood and undergrowth. Slash and burn clearing of the species that crowd out the slow-growing hardwood trees makes for an apocalyptic landscape, acrid woodsmoke choking entire valleys, the heat from still-burning sections carrying on the already hot, dusty breeze.

In principle, camping undetected in this region should have been easy as the tiny villages were separated by miles of scrub jungle. In practice, the steep, overgrown hillsides offered few suitable niches. With persistence I found a spot beside an apparently little-used footpath into an area of barely smouldering forest. The sultry evening air was heavy with night-blooming jasmine and earthy vetiver. Square-winged storks loped high overhead and hoopoes flitted through the treetops. I pitched the tent, inner only, as night drew a veil over the hillside and listened to the wild sounds of the forest, occasionally punctuated by the report of a hunter’s rifle in the valley far below. After midnight some still vigilant part of my lizard brain roused me from a dream. I sat bolt upright just in time to see through the gauze tent door a group of six or seven figures moving quickly but silently in single file along the path by torchlight, heading straight towards my tent, every one carrying either a large curved knife or a gun. My brain froze. My tent, bright white in the moonlight was unmissable in torchlight. Within seconds the front of the party had entered the clearing in front of my tent. No sound was uttered and none of the figures who followed even shone their lights in my direction, each on the heels of the man in front. In a moment they passed through my camp like ghosts, and I was aware only of the thundering of my heartbeat.

Once clear of this ‘pointlessly hilly’ terrain, as a passing Latvian cyclist adroitly called it (every 100m height gain is immediately squandered with a steep descent), I enjoyed a couple of days of textbook perfect cycle-touring. Solid, unhurried mileage; great roadside food; lots of friendly banter with locals; cold beer and superb wild-camping; the shrill, urgent call of the brainfever bird ever-present (a.k.a. the common hawk-cuckoo; a reclusive ragamuffin thing that tries to look hard by pretending to be a sparrowhawk; its call is said to sound like ‘brain-fe-ver’).

I cruised into the tourist town of Bagan looking forward to a few days off, especially as I was to be joined there by the amazing and delightful Tara, an adventure cyclist I had met six months before in Bishkek, who was now travelling through Burma in the opposite direction (read her beautifully written and photographed stories from Burma at www.followmargopolo.com). What with obligatory wat-spotting outings (Bagan has thousands), the planned two-day furlough slid seamlessly into four as the carb-loading and companionship exerted a strong gravitational pull. Before long, Michael (www.walthi.ch/en/), a passing Swiss cyclist, was lassoed into our happy little clique and the seeds of future riding partnerships sown.

Finally reaching escape velocity from the pleasant interlude in Bagan, I crossed the Irrawaddy and knuckled down towards the Indian border before my visa expired in a week (are you sensing a theme here?). West of Pale the patchy road pitches and plummets over thousands of vertical metres. I have ridden hillier terrain and indeed hotter conditions, but never before have the two been combined to such enervating effect. Toiling up and down brutal 25% grades in the daily 40°C heat, roiling nausea made solid food a trial. The bike was suffering too: the chain groaning through schizoid shifts from granny-ring to high gear and back, and heavy braking on the steep, sketchy descents overheated the wheel rims and exploded my inner-tubes. On a steep, lumpy descent I overtook a fully-loaded flatbed HGV. Moments later the front tyre hissed from seventy to zero p.s.i. in five seconds flat and I skidded both feet on the ground trying desperately to keep the unwieldy bike upright. Finding space but no shade for a pit stop, the replacement tube went the way of the first with a loud bang before the wheel was even back on the bike – the intensity of the midday sun having heated the barely-cooled wheel rim back to intolerable temperatures. (Following thorough inspection this is my best hypothesis. For a while I wondered if the pressure gauge on my pump was faulty leading me to overinflate the tubes; the rubber seal in the pump was also seizing in this heat causing considerable concern). After a sleepless night in a grotty guesthouse in Gangaw, barely aware of my surroundings I cycled 20km out of my way before I realised I had gone wrong. Stumbling from one cold-drink stop to the next (refrigeration was my holy grail in these parts) and barely able to take solid food, I broke my golden rule and camped early, watched over by my familiar the brainfever bird, squawking ceaselessly at the moon (the bird not me).

But the rewards of this region more than compensated for the hardships. Away from the main tourist destinations foreigners were nowhere to be seen. Off the main drag in the hill villages I was the first outsider some people had ever encountered. Life here continued as it had done for generations, bullock carts and human-labour still the main motive power. Make no mistake, the interior of Burma is beset by grinding poverty, but that Burmese smile – sometimes a ghastly blood-red grin in a ghostly thanaka-painted face; sometimes white teeth amid a lustrous milk-coffee complexion; mostly somewhere in between – was always forthcoming. Food was always generous and excellent in Burma, and local restaurants were just as likely to refuse to accept payment altogether as they were haggle.

I cut the corner of Chin state along boulevards lined with giant peepals (bodhi trees) and orange-flowered ashokas, every other building a church from one of a hundred denominations. A long, green snake slid out of the verge in front of me. Before I could even react it had taken the full force of both wheels, 130kg concentrated on less than two square inches. I didn’t even feel the bump. Nervously I glanced back in time to see a reptilian tail disappearing into the grass. Christian state or not, the forces of instant karma held sway here as twenty minutes later I took a bad line on one of the treacherously-surfaced wooden road bridges and almost fell to my death between the open side struts, the front wheel wedged solid between two decrepit pieces of tarmac top-dressing, my groin brought down hard against the headset. I dragged the bike to safety and lay foetal for ten minutes, sobbing and cursing pathetically. ‘Just is the wheel!’.

At the Burmese border town of Tamu I had a welcome reunion with Sonya and Gabriel, a friendly Swiss couple taking a break from bike touring to backpack in Asia, whom I had met twice in Yangon and then at a roadside café that very morning. A shared hotel room kept costs down for all, before we engaged with border bureaucracy next morning. A new and only sporadically open border crossing, the Indian side is still not set up for tourists, the border security, immigration and customs offices scattered around the town, the officers supposed to be staffing each scattered elsewhere. ‘Too many cyclists!’ the affable young customs officer opined, ‘I haven’t had day off in months’. The army in the form of the estimable Assam Rifles was a visible presence everywhere in the Indian states of Manipur and Nagaland, trying to control the barely supressed political unrest from separatist factions agitating for independence. At roadblock after roadblock the Rifles were courteous and helpful – filling my water-bottles in exchange for selfies, the usual drill – as I hacked across the steep Manipur hills to the state capital, Imphal. There I stayed with Warmshowers host Abow and his family, who gave me the most generous introduction to Indian customs and need-to-know, and where, guided by Abow’s patient hand, I was able to repair and replace dilapidated kit. Against my expectations and naïve stereotypes, gleaned from admittedly scant research (i.e. Slumdog Millionaire), India was exceeding my expectations admirably. The FCO travel advisory against all travel to Imphal seemed utterly incongruous with my experience there – just as well really.

With Kathmandu and a hiking trip into the high mountains now firmly in my sights, I turned west across the plains of Assam, making for the capital, Guwahati, on the banks of the eternal Brahmaputra. Road signs urged conservation of indigenous wildlife: monkeys, elephants and tigers. I smiled unconvinced, but within ten kilometres I had seen from my bike two out of the three, and decided to defer camping until clear of the forests. My passage coincided with the Hindu Holi festival, a riot of colour and all night parties. I gave a wide berth to a group of dye-daubed and visibly drunk lads, who jumped off their motorcycles right in front of me, trying to recruit me into their debauch. The commotion startled a goat kid, which bolted into the road right under the wheel of an oncoming motorcycle. Braking hard enough to lift its back wheel off the ground, the speeding motorbike veered towards me and I lunged into the crowd of revellers screaming blue murder at the top of my lungs. Freeze-framed permanently in my memory, this near miss (near hit? I can never decide) did not favourably dispose me towards Holi revelry, so it was with relief that I found a place to pitch my tent in the common land amidst a predominantly Muslim village, an oasis of calm amidst the chaos. Or so I thought. At 8pm the shrill, soaring vocals of Hindi dance music carried across the field from the neighbouring village, heavy bass and percussion penetrating my ear plugs and continuing throughout the night. At 6am I emerged from my tent, bloodshot eyes meeting the curious gaze of local residents waiting outside to see what kind of creature lives in a shell like this.

In a big day’s ride to Guwahati I battled through the heat, dust, a nasty bout of food poisoning and finally disappointment at the cancellation of a tentative Warmshowers arrangement for the night. Trusting to providence I cracked on regardless. Ten minutes later a motorcycle pulled alongside me and I took a deep breath ready to answer the usual, predictable interrogation for the twentieth time that day (‘Not too close please! … England … England, Angrezi … Yes, honestly … Guwahati tonight … No it’s not too far to cycle today … Yes by all means you can have a photograph, but I can’t stop for it … Keep your distance mate! … No, I’m sorry I can’t keep stopping all the time … Sorry, no … No … No! … There’s no need to be like that about it … Nice to meet you too.’)

But to my surprise the rider gave me plenty of space, simply asking if I was okay and where I was going. Sufficiently disarmed to start a proper conversation, I learned that Manash was going home to Guwahati, and on hearing that I was looking for a place to stay he immediately offered to host me, gave me his phone number, enquired after my particular narcotic preferences and sped home to prepare the ground. Four hours later the discomforts of the road were but a pleasantly blurred memory as I was first whisked to a local ethnic restaurant then plied with beers and songs by Manash and his flatmates.

My run of good luck continued: next day I was able accept a kind offer from Warmshowers host, Ritu, who was now back in town. Although I planned only a couple of days recovering in Guwahati, Ritu, his lovely wife Nomi and their circle of good friends and neighbours were far too welcoming to allow me to leave after such a brief acquaintance. My strength returned by the day thanks to the delicious meals from Nomi and neighbour Vikash. By the time Swiss Michael (from Bagan) splashed into town I was more or less ready to hit the road with him to Nepal. Ritu’s generosity extended to arranging a stay with his family and friends in his home village 110km along our outbound route, the comfort especially welcome as I was still way below 100% after my (probably self-inflicted) food poisoning on the way into Assam. The days were increasingly muggy and the towns more the ‘friendly chaos’ of my expectations. We placed bets on the size of crowds that puncture repairs would draw (my initial bid of 25 was way too low – Michael cleaned up as the crowd topped 40). The gravid pre-monsoon skies finally burst above our first camp north of the Brahmaputra. We pitched our tents just in time to find that neither one was still proof against a deluge of this intensity, and I sat soaking up puddles as the storm beat a thunderous tattoo on my leaky snare-drum of a home.

In the shadow of Bhutan we had a final lunch together, Michael planning to spin up the hill to Darjeeling and then take backroads to Kathmandu rather than my beeline. I asked offhandedly whether he had considered a foray into Sikkim, the northern mountain kingdom that became a state of India in 1975. Mulling the idea, he read aloud passages from my copy of Himalaya by Bike, piquing my desire to get off this sweltering plain and up into the hills, until I could bear the provocation no longer. Everest wasn’t going anywhere in the next few weeks, I reckoned. We shook on extending the partnership for another week up to the Sikkimese capital, Gangtok. As befits the home of Kangchenjunga, the world’s third highest peak, Sikkim is seriously steep (Kangch straddles the border with Nepal). The muscular, low-gear riding put as much strain on bike as rider. In an impressive channelling of beast-mode, Michael snapped his granny ring – something I would not have believed possible had I not seen it with my own eyes!

Border Roads Organisation signs in India and Burma

My first attempt to return to West Bengal was rebuffed by border police at Jorethang. Rather cheesed off I detoured to Rangpo and almost snapped my own chain ring on the convex two-vertical-kilometre climb from the River Rangeet up to Darjeeling. The ‘queen of hill stations’ was scarcely more scenic than a dozen other towns I had passed through in India, but my exertions were repaid by a chance encounter in a bar with four musical Anglophile former school friends (brainwashed by the Jesuits if you ask me!), who gave me a rare insight into town and country politics. Darjeeling has as at least much in common with Nepal as it does with the rest of India, three of my new friends’ surnames revealing their Nepali heritage.

What goes up must come down, so I tipped the bike into Hill Cart Road – two vertical kilometres of switchbacks (so my innertubes survived) down to the dustbowl of Siliguri. Breezing through the laid back immigration post into Nepal (three months visa on arrival, happy days), I found the towns of the Terai, the southern lowlands of Nepal, pretty uninviting; all honking buses and motorcycles swerving about, yapping dogs, pushy hawkers and noisy spitting. On the occasions when I was forced to stop for refreshment the interactions were good-humoured, but prices were unpredictable and I found the constant need to haggle both cynical and tiresome. On the other hand, camping in Nepal was a treat compared to lowland India. True, it was now uncomfortably warm but I didn’t need to try so hard to conceal my intentions when scouting for sites. Nepalis just nodded, offered suggestions and water and left me to get on with it. On my first night, two guys wandering in the woods warned me to be wary of elephants crashing about round here, but seeing no real evidence of any hazard I just picked a grassy hollow and got my head down. Hearing a tree crashing to the ground nearby soon after, I stuck my head out in time to see the two guilty-looking fellows dragging their illicit firewood away under cover of darkness. Pesky heffalumps! But then later as I read in my tent the ground started to shake, subtly but sickeningly. Convinced that pachyderm oblivion was afoot, I shot out of the tent expecting to be confronted by six pairs of baleful eyes, trunks swaying menacingly. But not a creature was stirring (not even a mouse) and I remembered that I was now in an active earthquake zone; I later heard that there was a 4.3 magnitude tremor that evening. But there was something to see: fireflies in greater abundance than I have ever seen before or since. Completely surrounded by hundreds of iridescent green motes like magic dust, I was too awestruck to think of filming it at the time.

By day the Terai dragged on, hotter, dustier than ever. Inevitably sickness caught up with me before I could escape into the mountains to the north. Amongst my lowest points in recent memory was lying in a pestiferous woodland clearing for several hours during the hottest part of the afternoon, hiding from the constant attention that I received off the bike, wracked by some godawful enteric bacilli, without sufficient water to stay put but scarcely able to continue (Radio 4 listeners will appreciate why I am considering changing this blog’s name to ‘Crossing Continence’. Ho ho, indeed). Next day, at the turnoff to Kathmandu the wheels almost fell off again, figuratively speaking, as heat exhaustion threatened more serious consequences. I took refuge in someone’s front porch, poured half a bottle of water over my head and sat sipping the rest for three hours until the pounding in my head subsided. By some miracle, just as the family whose front step I occupied started to view me as a permanent garden ornament, I felt hungry and mobile again. From here I gained altitude with every kilometre of sinuous mountain road, and for two days I dodged the bags of vomit jettisoned from passing mini-bus windows. A few pollution-choked miles on the final approach notwithstanding, I was home free to Kathmandu.

Ah, Kathmandu! Some place names have particular resonance for me, a romance conjured not so much from any informed notion of their character as boyhood dreams of travel to intrepid, exotic sounding places. The Timbuktu effect if you like. Virtually anywhere ending in the letter ‘u’ qualifies straight off the bat. Places with literary or cinematic connections. Anywhere that Willard Price sent his precocious Hunt brothers. I have occasionally chosen routes just to tag some boring modern city where a once great civilization existed. Such places sometimes represent true milestones on my trip, and Kathmandu is firmly in this category. Although my travels in Asia are far from over yet, arriving in Kathmandu felt like the end of a big chapter. More importantly it signalled the opening of a new chapter and the imminent fulfilment of a lifelong ambition: to trek in the Himalaya and see up close the world’s highest peaks, to live for weeks on end free of motorised transport, away from the noise, the speed and pollution of the modern world.

‘Heaven, one to beam up’.