Don’t worry be happy

From the front passenger window of a speeding jeep I look for familiar landmarks from the last month’s ride. It is a moonless Kashmir night, the Milky Way shows bright against the endless black of the Himalayan sky. The jeep’s headlights throw a sickly greenish cast on the valley walls. We could be on an alien planet. I am extremely tense. My bike is tied amateurishly to the roof-rack. Six other bikes are more securely attached, but all are being shaken loose every time the jeep hurtles over rocks and corrugations. The driver is hell-bent on covering the whole seventeen hour journey to Manali in one long push; there is no co-driver. Five other passengers, all middle-aged Indian men, cram into the back seat. They talk non-stop for the first three hours after we leave Leh, the loudness of their voices makes my ears ring. After ten hours we make the briefest of stops to drink sweet chai, re-tie the bikes and pee.

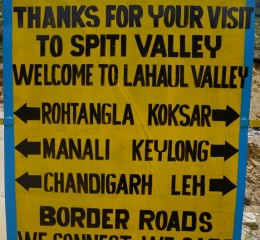

With dawn comes new hope. The improving light surely improves our chances of survival. After fourteen hours on the move we reach the Rohtang La pass, meaning ‘pile of bones’ for its high fatality rate. Our driver has been awake now for over twenty-six hours and is looking the worse for it. The Rohtang is serpentine and rubble-strewn with steep drops and no parapet. Workers, women mostly, sit on the uphill verge breaking rocks into smaller pieces with hammers. I have just reprimanded the driver again for going too fast on this awful surface, which is shaking the bikes loose, so I am grateful that he is behaving and staying in the convoy of vehicles grinding up the switchbacks. My eyelids are impossibly heavy. Suddenly we are off the road. The jeep tilts at a sickening angle as the nearside wheels start to ride up onto rubble on the uphill side of the road. In a split second I grab the steering wheel, pushing hard over to the right, yelling at the driver to wake up. We swerve back into the middle of the road. Thankfully there is nothing coming the other way and the driver doesn’t overcorrect and take us over the lethal downhill edge. He refuses to stop for a break, insisting that the danger is from going too slow, making his concentration wander. Clearing the col we descend through prehistoric mountain forests rent by waterfalls hundreds of metres high, but my eyes stay glued to the road as I fight the fatigue.

Finally, Manali. I unweave my bike from the tangle of metal on the roof-rack. Amazingly the only damage is the loss of a handlebar globe ornament. I cannot bring myself to shake hands with the driver or his mate, I am too angry at their incompetence and callousness. They clumsily throw the other bikes that they have been paid to safely convey into a trailer and disappear into the afternoon melee of revving engines and honking horns. Stale adrenaline and exhaustion leave me shaken and emotional as I pedal up the hill to find a place to crash out. The last seventeen hours were the worst journey of my life. Perplexingly, my fellow passengers seemed unfazed. Indians are much less squeamish about death than Westerners, as anyone who has heard of the burning ghats at Varanasi will know, largely due to the tenet of reincarnation in Buddhist and Hindu thought. I myself do not believe in reincarnation. Nor do I trust in Vishnu the Protector, Ganesha the Remover of Obstacles or any of the pantheon of deities to whom Indian drivers offer up prayers for their safe passage. This, it turned out, placed me at considerable disadvantage on the mean streets of India. It was a steep learning curve.

Rewind two months.

The Indian embassy in Kathmandu had sent me packing with a flea in my ear, denying my application for a six month stay, stingily granting only three (especially galling as I’d had a six month single-entry visa already from Burma). After almost two months off the bike I laboured over backroads to Pokhara, Nepal’s second tourist town, for last minute catch ups with former trekking buddy Joan and some writing. Inertia pinned me even as my Indian visa-bomb ticked away. I was reluctant to return to the heat and noise of the Terai lowlands, where two months before I almost succumbed to heat exhaustion. Now in June it would be even hotter. For nine days I stayed glued to my laptop in Pokhara’s lakeside cafés, evenings drinking strong Nepali beer with Joan and American searcher Salem. I conceived a hare-brained plan to power across the steamy lowlands and up to Shimla, 1200km away, in under ten days to celebrate my birthday. My pedaling momentum was soon regained, but the oppressive humidity and mosquitoes made camping a miserable enterprise. Cheap guesthouses ($5–10 a night) were a better option ‒ a fan (no chance of aircon at that price) and cold shower making the nights more bearable.

Through daily thunderstorms in Bardia national park I rode hard, using every last drop of daylight. I made camp at the edge of the forest as darkness closed in and spent a restive night in the stifling tent. Sneaking back onto the road in the morning, I realised that I had camped directly behind an army checkpoint, within the area of the park designated as a tiger sanctuary. Somewhere near the Indian border I stopped for a late lunch at a roadside restaurant. While food was prepared I got the usual interview from the kindly owner. When he heard I was British, he stopped mid-sentence, pointed at me and said “you are out of the EU!” My heart sank. They put an English news channel on TV and my face must have registered my sorrow. The Nepali staff made conciliatory noises, but everyone wanted to know “why?” They couldn’t fathom why any nation would want to leave such an influential club and I couldn’t give them a convincing answer.

Not all news from the outside world was unwelcome. Throughout my time in Nepal I had stayed in touch with Tara, the Canadian cyclist with whom I kept crossing paths, first in Kyrgyzstan then in Burma six months later. She was now working in Australia to earn funds for more cycle touring and had accepted my invitation to cycle together in the Outback. Sharing our thoughts and plans for that expedition, it became obvious that we both wanted to be more than just friends. I could hardly wait to see her again. Suddenly, the fact that I had to leave India in less than three months was a blessing. To be able to talk to someone who understood the trials of long term solo cycling was enormously sustaining; my mood and my energy levels soared. Singing my head off like a halfwit, I made excellent time to the border town of Mahendranagar, where I stayed with new Warmshowers host Shiwasreet and his father Padam. Dreaming of his own bicycle adventure, Shiwa soaked up touring tips in exchange for a superb dal bhat – my last in Nepal.

Compared to rural west Nepal, the Indian state of Uttarakhand is industrial and densely populated (although the north has mountains and national parks). State tourist board signs proclaimed ‘Uttarakhand Simply Heaven’, but I finished each day with a thick layer of dust and soot on my face, arms and legs. Cows nosed through mounds of rubbish while dogs and monkeys scrapped over territory and food. As in the Terai, camping here was out of the question for non-masochists. Every day I prayed for rain to cool things down and sought village stand pipes to dowse my clothes, which would dry on me within half an hour. The dirt, the heat, the noise; this was beginning to look like the India that I had braced myself for. Friends had warned me that my notions of hygiene and personal space would make for a tough time in India (‘Tell me how you feel at the end of your first day there’; ‘Dan in India, this I can’t wait to see!’). I tried to let it all wash over me. At obstructions and level crossings I waited patiently as tuk-tuks and motorcycles filled every available inch of the road, making it almost impossible for traffic to get flowing again. I smiled and shook my head as I watched cars stall mid-manoeuvre, sideways across two-lane highways, the driver pausing to text or talk on his phone while the traffic once again clogged every pore of roadspace. I was repeatedly surrounded by a tinnitus-inducing cacophony of cars, lorries, motorcycles; hot, revving engines and exhausts spewing fumes, everyone honking their horn like a maniac.

But against all expectations, I was coping well. I had a song in my heart and the greatest mountain ride of my life ahead of me. I congratulated myself on my adaptability and resilience. Predictably, pride comes before a fall. All day I had been harangued by close passing traffic. The intensity grew as I approached the city of Haridwar; hundreds of thousands of people converging there to bathe in the holy Ganges river and visit shrines. The inbound lane on the bridge over the Ganges was gridlocked. I hung back from the choking exhaust of the lorry in front, but the car behind kept pushing me forward. I turned and looked the driver in the eye, shook my head and indicated with a shrug that none of us could advance on our side of the road. He honked his horn impatiently and nosed forward again. I turned and shouted to just wait. Now his front bumper was hard up against my rear panniers. Another push. The bike lurched beneath me and I snapped, hammering the car’s bonnet with the flat of my fist, yelling to keep some effing distance. The driver looked terrified, and for a moment actually stopped honking his horn. I pulled out into middle of the road and squeezed through the oncoming traffic to escape before I did some actual harm. It had taken just over two days, but I was reduced to the state my friends had predicted.

In Rishikesh I ate in a canteen restaurant so crammed that the waiters had to insinuate themselves bodily between back to back diners and pass plates over our heads. The hubbub of multilingual conversation was bewildering. The walls were covered in garish 3D pictures of animal gods, flower garlands and faded menu photographs. The Southern Indian chap opposite me had been to university in England and confessed even he found this scene a sensory overload. He commiserated about the EU referendum. “You must be sad, Britain’s favourite pastime is making fun of how stupid the USA is, but you can’t do that anymore can you”. (This was still a few months before the U.S. general election. Every cloud, hey?). Outside we followed a procession of costumed musicians, papier-mâché deities and animals. On a bejewelled and painted elephant rode a youth in an immaculate white suit and cobalt blue turban. He looked every inch a prince from some Rudyard Kipling story. I asked my dining companion why the princeling had such a sad face, was he being publicly shamed or something? On the contrary, explained my friend, this was the boy’s wedding parade, his sour expression a reflection of his onerous duties. “I would like to give him a slap for being so ungrateful”, he added.

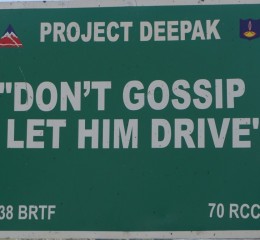

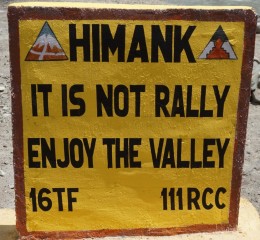

Always during my travels in India I found that off-the-bike encounters with people were enjoyable, good-natured, and easy going. English was widely spoken and almost everyone was talkative and playful, albeit with no concept of privacy or personal space. It was just that those same people, in charge of a moving vehicle, became heedless, honking maniacs. Day after day I witnessed calamitous, cretinous driving on a scale impossible to fathom. Overtaking an already overtaking vehicle on a blind bend. Motorcyclists on the phone, their helmets perched on the back of their heads like an alien outgrowth. Anything was permissible so long as you keep pressing that horn. At the start of the serious ascent into the foothills above Nahan, I peeled off my sweat soaked T shirt and sprawled in a roadside shelter for ten minutes peace and recovery. A group of teenage boys on motorcycles showed up, buzzing around me like flies. “Please, take your sunglasses off”, “Ahh, blue eyes, blue eyes!”, “I want a selfie with you. You have real nice body, man”. Awkward and exhausted, I had no option but to go with it. “Why are you not married?”, they asked. “Are you waiting until you are 100?”. Later, riding into the dusk, a white Landcruiser came alongside. The enormous bald head of the muscly Rayban-sporting driver leaned over to ask was I okay? He gave me his mobile number and he urged me to call him when I passed through his town the next day. “You will be my honoured guest. I will give you pure marijuana!”, he proclaimed with a plosive flourish of his fingers, like a stage magician.

Things were looking up. Within a day’s ride of Shimla I camped in the cool air of 1400m for the first time in months. On this my second birthday away from home I awoke in a hillside woodland, a big improvement on last year’s sorry celebrations in the middle of the Kazakh desert. Mr Big showed up again, checking I had his number and “remember, pure marijuana”. I reassured him that I had the number. But this was going to be my party and I decided I’d rather cycle up the mountain to Shimla, as I’d promised myself. Arriving at tea time, I pushed my bike through the crowded mall up to Scandal Point. I was accosted by a hotel tout, a wizened looking Pathan in combat jacket and fuzzy black chin curtain. I dismissed him straight off the bat, telling him that my budget was too small for him to be able to help me. He challenged me to name my price. We eventually agree 2000 rupees for three nights. “Okay meester, follow me”.

Izat says his name is Pashto for ‘respect’. He walks incredibly fast, talking to himself animatedly when he is not shouting into his phone. We go up narrow, steep streets where he has to help me push my heavy bike, until we arrive at the bottom of a long flight of steps. “You are kidding me”. “No just up here, I help you, no problems”, he wheedles. Not willing to commit yet, I lock the bike to a fence and we climb three flights to reception. The manager asks for 3000 rupees. I explain that’s not the deal that brought me all the way up here. Twitching now, Izat insists that’s what we agreed. I tell him he’s a liar, but anyway forget it, I’m going to the youth hostel. They shout at each other while I pick up my bag and head to the door. “Please, sir, it’s okay. For you we make it 2000”. “Final price?”, I ask, “No surprises?”. “Final price”. It’s 8pm now and I’m fit to drop after a 120km uphill ride, ten days’ consecutive hard riding in my legs. Returning to my parked bike, Izat pinches my arm and holds out his hand. “Baksheesh” he demands. I laugh in his face. “Bakseesh!”, again forcefully, pulling my sleeve. I set my jaw and shake my head, scowling. He storms off down the steps, frothing and raving. I order a curry and a bottle of Old Monk rum and collapse into bed.

From Shimla, the scenery was about to get much more interesting. The Manali to Leh highway is a big tick on any Indian bike tour, with the added thrills of the stunning Kinnaur, Spiti and Kashmir valleys. In front of me stretched the best part of 1600km of remote, rugged, high altitude riding, right into the heart of Great Game country. Actually make that 1200km, the final section from Leh to Srinagar having been declared off limits in the last few days. The army had shot several guerrilla fighters in NW Kashmir. Curfews were now in place and the frontier with Pakistan was on high alert, but Leh in the Ladakh part of Kashmir remained open for business. Leaving Shimla I resumed my nerve-jangling ride. Near Narkand a 4WD SUV hurtled past me down the road drifting between lanes. I turned to watch as it caromed off a high kerb and flipped over, landing on its roof. The wheels spun wildly as a family of six climbed out of the windows, dazed but apparently unhurt.

Kinnaur valley is steep and rocky. What little flat land exists is occupied by army and road engineering (GREF) bases, so I was was not camping much on this part of the trip. My mood and ability to cope with traffic stress fluctuated in direct relation to access to decent food. After a tortuous morning riding up and down a mountain to bypass a landslip, I ferreted out a hole in the wall dhaba (a primitive cafe or truck-stop) in Karcham. It looked distinctly unpromising, but in India appearances are often deceptive. Working in dingy squalor with a single burner on top of a gas bottle, the grizzled old man produced the most exquisite meal of chola batura (chick peas and puris), pickles and paratha that I found anywhere. He chuckled and slapped his big round belly, beaming proudly as I scoffed three plates and a dessert of barfi cubes (sweets made of condensed milk).

On a whim I made a foray up the side valley of Sangla, where I intercepted Guru and Pavan, cycling guides from Bangalore out recceing new routes for their tour company. Heading my way with their driver, Om, it was nice to share hotel rooms, beers and stories for a few days, although I think Pavan sometimes wished he was on his motorcycle. Slowly I worked my way towards the confluence of the Sutlej (flowing from China, barely three miles away) and Spiti rivers. Roadblocks and landslides were increasingly frequent. Sometimes I broke the bike down and portaged the bags across the debris, sometimes I waited along with everyone else for it to be cleared by the GREF work gangs.

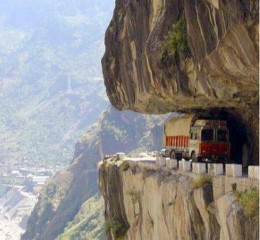

Near Recong Peo, where the road passes through a ledge carved into the cliff, a lorry tried to overtake me in the narrowest section. The driver was reluctant risk his own life by moving too close to the cliff edge, so squashed me against the solid rock on the inside instead. I felt the back of the bike being pulled under the truck, and I hammered on the passenger side door yelling for the driver to stop. Miraculously, he realised something was wrong. The sharp metal fender of the truck had torn a hole in one of my rear panniers, but otherwise I seemed to have got away with it. The driver started to berate me for not getting out of his way, no remorse or concern for almost killing or maiming me. I went ballistic. Sensing there was a real danger I might throw him off the cliff, he jumped back in the cab and slithered away while I hopped and bellowed.

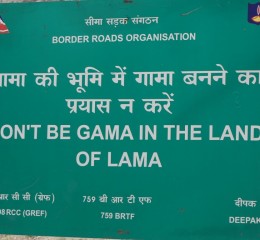

This wasn’t working. I felt powerless to defend myself against these metal monsters. The rules of the road as I understood them did not apply here. Here, big is boss. The wider, the heavier your vehicle, the more other road users should watch out and clear off, and I was nearly at the bottom of this pecking order. If I was going to stay alive I needed to change my attitude, be more humble and get off the road more often. Except, there were long sections of this route where there was nowhere to get off the road, as above when I was trapped in a cliff edge gallery. Throughout my trip I had refused to allow myself to become complacent about the risk posed by other road users. Although I never saw the need for one before, I had fitted a handlebar mirror as a constant visual reminder of the main danger on my travels. Not malaria, bandits, corrupt officials or any of the other exotic hazards that people dream up. Just plain old motorised vehicles. The mirror is my memento mori. Ironically, in India, you don’t need to be reminded that you are mortal. It is hammered home by every passing truck and car. Amongst motorists, ordinary life-preserving caution is a luxury, courtesy rare and patience non-existent. Not for the first time I was butting up against a new set of cultural norms, importing my own sense of entitlement and correctness. To survive, I needed to accept and adapt.

Brooding on the fragility of life I swung north near the Tibetan frontier. Once again the road became a single-lane gallery, known here as Taranda Dhak or the ‘Sandwich Road’ ‒ a sinuous balcony that climbs steadily for several kilometres of blind corners and sheer drops. Through the iconic arch of Kinnaur Gate ten motorcyclists roared past me, engines echoing throatily against the rock walls. I steeled my nerves. From behind I heard the rumble of heavy axles. Not wanting to become sandwich paste again, I sprinted to safe haven on a patch of gravel beside a barrier. Five supply trucks thundered past, followed by a dozen or more army trucks. Once clear of the gallery, a vertical kilometre of switchbacks led up to the pretty mountain village of Nako. Recalling the trouble I’d had at altitude in Nepal, I found a quiet homestay for a couple of days’ acclimatisation. I’d had a good run of health for the last few months, but no Indian tale would be complete without a night spent puking one’s face off. This was that night. Scarcely strong enough to walk into town in the morning, my day off became a woozy quest for palatable nutrition.

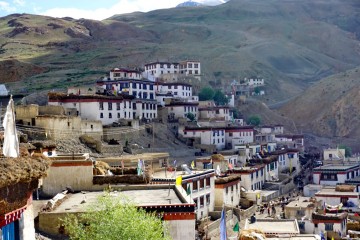

Enfeebled, but at least continent, I traversed the Malling Slide without incident (a perennially unstable landslide area where a tag team of bulldozers continuously clears the road, letting traffic through between thunderous shunts over the edge). I glided down to the pleasantly tree lined village of Tabo. Towns here were Tibetan in appearance: flat roofed peasant small-holdings, a few homestays and tourist businesses. The workaday bustle and thrum of the Kinnaur towns was now behind me. As in so many other disputed border regions, here ethnicity and culture transcend cartographic boundaries. Physiognomy, dress, food and tradition in the north of Himachal and much of Kashmir are more influenced by settlers from the Chinese-Tibetan side than by the Indian hinterland.

I detoured up the scenic Pin valley, battling a ridiculous headwind to the village of Mudh for a couple more nights’ acclimatisation and contemplation. It was not quite the remote mountain sanctuary I envisaged; the homestay was full to capacity with an international crowd of young backpackers and motorcyclists. The owner was a podgy, indolent looking fellow, but the place was run entirely by his children (as is so often the case in Asia). His twelve year old son and teenage daughter retained their equanimity admirably in the face of the most trying requests from high-maintenance tourists. Half the guests were Indian (domestic tourism in India is huge); cliquey groups of semi-stoned Israelis on jeep tours and European twenty-somethings on clapped out Royal Enfields made up the rest. On the morning I left, the children had taken an early bus to the birthday party of a local celebrity monk, leaving the owner to deal with twenty demanding Isrealis. They wanted to pay separately for food ordered communally over three days. I think he may still be working out the bill now.

In Kaza all my budget hotel recommendations drew blanks. I was slumped over a table when I noticed two guys outside looking at my bike. Touring cyclists Dario, Swiss, and Juan-Francisco, Spanish, had just bumped into each other here an hour earlier. By coincidence Dario and I had almost crossed paths some fifteen months ago in Turkey. He had left a note on my bicycle while I was off exploring in a canyon. We’d exchanged a couple of emails but never met. The owner of the restaurant was a cyclist too and insisted my food was on the house, but regretted that he didn’t have a room available to give me too. No matter, JF had a room in a nearby hotel that he would share. Best of all, his place had actual working wi-fi, my first for a week. JF was travelling to collect stories to weave into a novel, finding characters and ideas to inspire him (see his beautiful video diary of this region). He had been three days already in Kaza, trying to get his front fork welded after one of his pannier rack bosses had snapped off on the notorious upper Spiti road. Precisely where I was heading next.

I made the obligatory side trip up to Kibber, so called “highest [permanently] inhabited village in the world connected by a motorable road and with a voting ballot”. I visited the hilltop monastery of Ki Gompe, but my heart was just not into sightseeing. I wondered if I was becoming jaded. Had I been too long on the road and needed a break from novelty? It’s fair to say I had seen a lot of Tibetan villages in the last year. One town paved with yak dung was starting to look much like the next. My motivation was sustained by random encounters with strangers, both locals and other travellers. Indians are open-hearted to a fault, and (so long as they are not driving) amongst the friendliest people I have ever met. After a very tough afternoon riding 80km on a rough road into a strong headwind I encountered a lone mountain biker, the vanguard of a local adventure tour group. Soon afterwards their support vehicle drew alongside, gave me some water and invited me to their ‘cottage’ in Losar, the village I was heading to that night. The cottage turned out to be a luxury lodge owned by tourism mogul Sahil. He generously gave over a sumptuous room to me at no charge, re-negotiating with his other paying clients for two of them to share a room. While Sahil’s chefs cooked up a banquet, the rum flowed and the hookah pipe circulated. Cyclists Arvind and Chirag urged me to join them for a day ride back to Kibber the next day. But as much as I relished the company, I couldn’t quite drum up the motivation to make an out and back ride to a place I had just visited.

In front of me lay the Kunzum La, the first of the 4000m-plus passes that stood between me and Leh. Cresting the pass on a chill grey afternoon I made fairly easy work of it despite a growing altitude headache. I had curiosity enough for one more side trip, to Chandra Tal lake. Impatient yobs in 4WDs tried to drive me off the road, honking and shouting at me. I misjudged my line on one of the river fords and soaked my shoes. Then I got a puncture. I spent an hour and a half scouting on foot for a campsite, searching in vain for a spot that matched the hype of this location. The lake was pretty, but the shore swarmed with tourists; it was like camping in a city park. I scowled from my tent, my woes compounded by a malfunctioning stove and disintegrating pannier bags. The beauty of the full moon that night, rising over the mountain, reflected in the fabled Moon Lake itself and sparkling on the glacier behind me was in retrospect worth the effort to get there. But at the time I was just peeved to be disturbed throughout the night by tourists out for torchlight walks (“Oh look, it’s that guy we passed on the road yesterday.”).

On the rough road back out of the Chandra valley I stopped to tighten a loose bolt on my front rack. In Batal I chatted with Delhi mountain-biker Arun, who generously offered to help me out when I arrived there in a few weeks. Out of Batal a block headwind of around 60kmh made riding in a straight line impossible, even if the surface had been good. But it was not good, not good at all. I had been told this part was “like riding on a dry river bed”, “so rough, even the goats won’t walk on it”. This turned out to be half true: it was like a river bed, but not a dry one. The road was covered in around 6 inches of water for about ten kilometres on and off, where unpaved fords had washed out sideways. I had to laugh. Either the wind or the road alone would have been a trial. Taken together, this was so preposterous that I knew it was hopeless to fight against it. Willing things to be different was getting me nowhere. But I couldn’t stay there. I gave myself up to the fates and bashed on blindly, unable to see where the front wheel was going through the tumbling water.

And then a strange thing happened. I was actually starting to enjoy the challenge of riding this, the roughest road I have ever taken on a non-suspension bike. Perhaps I became over-confident and rode a little harder than I should. But the next thing I knew, my front right pannier yawned away from the bike like a door on a hinge. On inspection, the lower fork boss (where the rack attaches to the fork) had sheared clean off, leaving the entire weight of the bag supported by only the top boss. Under the huge dynamic loading from bouncing along this road, the top boss had failed seconds later, tearing a 20mm ragged hole in the front of the fork rake, to which it remained half attached. I stared at the carnage in disbelief, my front right pannier hanging limply like a broken wing. What to do? Riding with only one front pannier was dangerously unbalanced. I managed to secure both front panniers on top of the rear rack, taking the tent and other lighter bulky items in the rucksack that had previously occupied that spot. The front end was now incredibly twitchy, but the system seemed stable. Well, let’s say, semi-stable. Many of the deepest ford over nullahs that cascaded across the road were unrideable without suspension and an engine. In sandals I wrestled the bike across one after another of these, the bike straining to rear up and capsize with 40kg all on the back. I limped on to Chatru and found a place to camp.

In the morning I cleared the last of the switchbacks out of Spiti Valley and descended through 5km of mud and diesel smoke in roadworks on the bottom few loops of the Rohtang La pass. Near Khoksar my wheels kissed the silky smooth asphalt and I gave a cheer. I was finally heading north on the Manali to Leh highway proper. I had survived Spiti! My front fork and rack were trashed, my panniers torn by truck collision, their attachment hooks barely clinging onto the bike any more. But I was through the worst of it now surely. Feeling like a conquering hero, I stopped at a roadside cafe in Sissou. Parked outside was a collection of bizarre bikes loaded with brightly coloured Otlieb panniers. A-ha! Fellow heroes of Spiti no doubt. Inside it was easy to spot French cyclists Seb and Ariane and their three children, Gaspard (12), Adelie (8) and Titoun (5). How quickly an heroic ego deflates upon meeting an eight year old who has just come through the same ordeal on a recumbent bike, whose only care is whether there is ice cream at the end of it.

Cycling to Keylong with la famille Langlais-Cristini was like joining the circus. I was used to people staring at me, the mad ‘Britisher’ on an overloaded ‘gear cycle’. But no one in Asia had seen anything like the contraptions that Seb and Ariane rode. Ariane and Adelie cycled together on a Pino tandem with Titoun on a Follow-me on the back. Gaspard rode his own mountain bike, while Seb towed a chariot-trailer for when little Titoun tired of pedalling. Vehicles pulled over, drivers and pedestrians cheered, everywhere crowds gathered for selfies with this remarkable ensemble. In Keylong Seb had arranged for a truck to take them into the remote Zanksar valley. Too rough for loaded touring, they had reserved a team of seven horses to carry their dismantled bikes and luggage while they trekked into deepest Kashmir.

My work in Keylong was to figure out how to improve my chances of making it to Leh, still 400km away over some of the highest roads in the world. Descents were now terrifying with a gaping hole in my front fork. The image of it collapsing like an elbow bending inwards as I hurtled down three vertical kilometres of switchbacks haunted me. The first two metalwork shops I tried wouldn’t touch it. At the third place a small group gathered and gestured at various solutions, drilling more holes into the fork being their favourite. I mimed what I envisaged – bracing and welding the fork front and back. The guy working the arc-welder was reluctant to get involved, shrugging that he had nothing suitable to use. I poked around the detritus littering the floor of the garage, eventually finding a piece of 1/8 inch mild steel. Bingo. I snipped with my fingers to show where to cut it with the grinder, then picked up a welding rod and held it against the fork. The surly fellow never cracked a smile, but he seemed to understand and set about the work. How I wish I’d taken my phone so I could video my beautiful bike on fire, the paintwork of the fork ignited by the sparks. For the princely sum of 100 rupees (£1) I got the bodge job I deserved. All that remained was to find out if it would it get me to Leh with my teeth, collarbones and wrists intact.

The names of the mountain passes ahead ran through my mind like a mantra, Baralacha La, Nakeela La, Lachung La, Taglang La. One per day for the next four days, simple. In Upper Zing Zing bar I wolfed bowls of slimy Maggi instant noodles and an omelet, feeling below par even at the modest 3000m altitude. As I gasped for air at the roadside on the Baralacha La (4918m), a motorcyclist pulled up beside for a chat. He was suffering with a bad headache too, having driven from Delhi in two days. Struggling to get his bike started, “these things need oxygen too”, he opined, seeming to think I would be sympathetic.

Over the pass, the Sarchu Plains shone green and gold in the evening light, a broad grassy strath flanked by sepia mountains. I eschewed the tented camps and continued to Sarchu itself, where I chatted with a friendly policeman who seemed happy to be posted there for the year. He gave me drinking water and recommended a good wildcamping spot near the gorge. The day had been a success, but I woke feeling awful – perhaps due to altitude, perhaps my own fault for going so hard the day before. In a grubby dhaba I forced down leathery chapatis and another bland greasy omelet, barely able to swallow.

Immediately to the north lay Kashmir. The urgent bassline and plaintive vocal of the Led Zeppelin song of the same name were stuck on a mental loop: “All I see turns to brown, as the sun burns the ground. And my eyes fill with sand, as I scan this wasted land”. Kipling’s description (in Kim) was similarly adroit: “Air and water are good, and the people are devout enough, but the food is very bad … and we walk as though we were mad ‒ or English. It freezes at night too.”

From the plain the infamous Gata Loops rose in twenty-one ponderous zig-zags up a scorched mountainside to the foot of Nakeela La (4937m). Hundreds of gaily decorated ‘jingle trucks’ churned along in bottom gear, bringing in supplies for the winter when the region becomes snowbound for seven months. Despite their ornamentation, these were no carnival floats. Convoys of these forty-tonne blocks of metal death snaked up the Loops for miles above and below me, hounding me off the road as they passed. Glad of the respite I let them through, later to squeeze past them all at another classic Indian log-jam at the top. I started to suspect that Indian drivers must be grandmasters at Tetris, given their ability to fill every square inch of roadspace when traffic stops.

Most of the terrain through which the Manali to Leh Highway passes has no permanent settlements, just army encampments and summer tent villages catering for tourists and supply convoys. Whisky Nalah is one such, a scruffy cluster of parachute tents, Nissen huts and abandoned vehicles at 4802m between the twin passes of Nakeela La and Lachung La. I dived into the first tent I saw and asked for tea and food – more gluey noodles and omelets. My head was pounding from the exertion of the Loops and Nakeela La, but I was in a bind. Pushing on over Lachung La (5077m) meant committing to another four hours of riding. The thought of spending a wretched night up here was softened by the serene, steady manner of the elderly Tibetan ladies who ran the tent. They gestured to an empty screened-off and cushioned room, where I could spend the night for a couple of hundred rupees. My fatigue won out and I collapsed in the back room, listening to the thin wind and the drone of passing engines. The peace was broken by two clueless Indian motorcyclists who bumbled in chilled to the bone, clad only in jeans, summer jackets and slip on shoes. They were in a worse state than me, complaining of dreadful headaches, having ridden hard from Delhi in under 48 hours, gaining almost 3000m altitude that day. Grown men in their late twenties, they told me proudly that they were medical doctors. They huddled together under a blanket and pathetically called out ‘Aunty!’ at half hourly intervals throughout the night, summoning the woman who ran the place to bring food or water or more blankets or tuck them in (‘aunty’ is a supposedly polite address used by Indian boys and men to an older woman, not necessarily related). All night they moaned at each other in the booming voices that pass for normal conversation in India. Repeatedly I pleaded with them to be quiet. In the middle of the night they tugged at my foot, waking me from a tortured sleep. “Mr Daniel, I need your water, I have to take pain killers”.

After terse goodbyes and a horrid breakfast I set an easy pace up Lachung La. Towards the village of Pang the road snakes through the Valley of the Hoodoos, where sandstone stacks had been sculpted by the wind into bizarre spires and phallic finials reminiscent of Cappadocia. Pang was another ratty collection of parachute tents. After the horrible night in Whisky Nalah I wanted the comfort of my own tent far away from motorised tourists. I chatted with Spanish bike-packer Alfredo travelling south to Manali, whose cheerful enthusiasm spurred me on to climb the switchbacks up on to the Morei Plain. It was a good decision. Once over the rim, my first tailwind in weeks propelled me across a vast thornscrub plateau to the salt lake at Tso Kar. I camped among grazing horses beside a freshwater stream and watched the sky turn from blue to purple to pink, the hues of the mountainous horizon following suit.

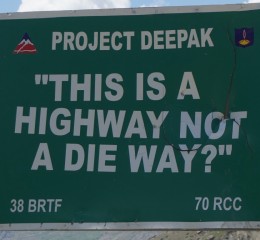

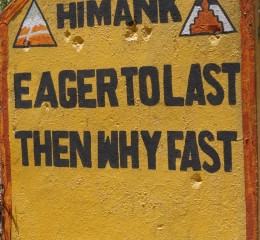

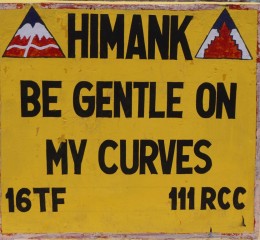

The big day had at last arrived: the Taglang La, the 5300m high point of the Manali–Leh highway. At the foot of the pass in Debring I took second breakfast with Belgian cyclist Sophie, who had bussed to the top and cycled down that morning. The gradient was gentle but relentless, a 20km crescent with the notch of the pass tantalisingly in view for most it. Once again I was beset by truck convoys, churning up dust and spewing diesel fumes. On a one lane section through roadworks a lone truck powered up the hill behind me. To the left the hillside dropped away into the valley, so I signalled my intention to duck off to the right between piles of stones in the roadworks. The driver didn’t slow down until the last second, evidently intending to swerve around me in the spot I had stopped. He hit the brakes hard and skidded towards me. The stink of vapourised tyre rubber coated the back of my throat and red mist filled my eyes. This was getting ridiculous. The barbarous indifference of these drivers was infuriating. ‘Don’t worry be happy’, the road signs advised, but this seemed to be taken as licence to dispense with anticipation and courtesy. Beneath the final approach to the pass another convoy of trucks was catching up with me. I took cover at the uphill right hand edge of the road and sat on a rock, waiting for the danger to pass. But now an overtaking car came barreling up the inside of the convoy, partly on the uphill shoulder, heading straight for my bicycle. I leapt in front of my bike and threw down the biggest rock I could find in the road to mark my territory, screaming to get over (or words to that effect anyway). At the last second the car swerved and stopped. Two greying German tourists got out to see if I was okay, a look in their eyes showed their wariness of my deranged state. Thanks for asking but your driver nearly ran over my bike, tell him to slow down and look where he’s going.

At the summit, my head was pounding from the altitude, adrenaline and sheer tiredness. Frustratingly, I was breathing some of the most diesel polluted air I have ever experienced up here on the roof of the world. As so often happens, just when things seem unbearable, the mood changed completely. The traffic abated and in front of me a well-surfaced 60km descent awaited. Trying to put thoughts of metallurgic failure far from my mind, I swooped down switchbacks that traced calligraphic curls into the Gya river valley. At a friendly homestay in Lato my room looked onto a field of swaying green barley backed by iron ore-tinged buttresses aflame in the dusk. In the morning I felt more human than I had in days. I coasted along the river gorge between mountainsides striated in otherworldly greens and reds, high above me a scalloped skyline like a basilisk’s crest. Around every corner more jaw-dropping geology revealed itself. At Upshi the Gya joins the upper Indus River. Past the Tibetan monastic edifices at Thikse and Shey I cruised a leafy lane parallel to the highway, an improbably serene end to a wild ride to Leh.

Capital of the Ladakh region, Leh is a natural citadel partly hidden from the Indus valley by topography. The transition from austerity to consumerism was disorientating at first. I weaved through the potholed streets, dodging hordes of tourists wearing ‘I got Leh’d’ T-shirts. For the umpteenth time, I was spared a tedious search for lodgings by a friend already in residence, this time Swiss adventurer Linda (lindabaer.com), whom I had met in the Pamir, barely 500km north of here, eleven months before. For the next three days I gorged on fruit, falafel and smoothies trying to expunge the hideous taint of glutinous Maggi noodles from my memory.

Since we met on the side trip to Sangla in Kinnaur valley, I had kept tabs on Guru, who was now bringing a tour group up the Manali to Leh road a few days behind me. He and his clients would fly back from Leh to Delhi, but his support vehicles would immediately return overland to Manali. I negotiated a place in one of these jeeps heading south, desperate to get to somewhere with a working internet connection to arrange the medical check up the Australian embassy had set as a condition of my visa. The die was cast. At dark we departed…

That I made it to Manali alive now seems a kind of miracle. During that terrible night I drew strength by focusing on kind words from Tara, who was waiting for me in Australia. I could endure the long jeep, bus and plane journeys stoically, knowing that they were necessary steps to get to her. From Manali I took the night bus to Delhi, a city I was certain I was not equipped to deal with. Predictably, I was physically shattered from the Spiti and Manali‒Leh ride. What I had not reckoned on was the mental toll taken by a long stint on those roads. My nerves and patience were shredded, my appetite for adventure all but finished. Delhi seemed like a final test of nerve. I needn’t have fretted. Warmshowers host Karan, himself a recent veteran of Manali‒Leh, assured me that all would be well . Intercepting my tuk-tuk, he gathered me into his spacious family home, where wife Mussarat, mum Anjeli, and dad Mukul extended every hospitality (see Karan’s stunning video montage from his and Mussarat’s Manali‒Leh ride). With the Australian visa medical knocked off the morning of arrival, I had a welcome week of R&R, hanging out and going for runs with Karan, and later playing tourist with Linda when she arrived by plane from Leh.

India is a country of intense experiences. It has a population almost twice that of Europe, in one third of the area. I would have felt short-changed had it not challenged the assumptions and prejudices in my world-view. In a lifetime of recreational risk-taking, high spirits and rank incompetence, I have had a few close calls to be sure. In India close shaves were a daily occurrence, but there they were not of my own making. But then, that’s not really true is it? There is always a choice and I had chosen this. But unlike the life-affirming clarity that comes from taking calculated, considered risks and the satisfaction obtained from knowing that you can handle potentially dangerous situations, the risk of being crushed by a moving vehicle is harder to rationalise. The best I can do is to suggest that riding defensively manifests differently in different cultures. Assertiveness and entitlement (to life) only work where there is respect for the most vulnerable people on the road. Elsewhere, acceptance and humility are more pragmatic. Cycling through Northern India brought me up sharp against the fact of human fragility, a memento mori I hope I will always remember.

Anyway, so much for philosophy. Who wants an ice cream?

1 April 2017 @ 06:25

Nice read. I’ve been in India for the last two weeks, and I can agree with yoh. It’s intense. Anyway, have a good and save journey Dan. You might try a paan 🙂 that’s delicious

5 April 2017 @ 05:42

Thanks Henk. Stay safe there, brother. Thanks for the tip. Korean food is among my favourite of any country so far.

31 March 2017 @ 20:59

Jesus Dan – I ‘m exhausted but enriched by reading that . The best one yet . I’m so looking forward to our start on the road later this year – smaller steps but hey – I ‘m prepared now aren’t I ?

1 April 2017 @ 03:09

Thanks for your continued support, Mark. NW India was the hardest section of my trip so far, partly because I was starting to feel burned out by continuous travel. You will have a great time in Spain.