Feast of Wire

Leaving Bishkek was never going to be easy after spending such an enjoyable couple of weeks there. On top of powerful inertia, Mirlan, my host in Bishkek, was adamant that I couldn’t leave on the Kyrgyz national holiday 24th September, urging me to stay for the family celebrations. But this time I had a real deadline to beat: the Chinese border was set to close for a week or longer – no one could say for sure – from 1st October for their main national holiday, ‘golden week’. Moreover, with every passing day it was getting colder in the mountains that I planned to visit in the south of China, so further delay seemed unwise. I had six days to make the dash from Bishkek to Khorgos, the Chinese border town, before the country was effectively locked down to overland travellers. This was my introductory encounter with Chinese funny business bureaucracy, and I couldn’t help but wonder how such a move would be perceived if Britain were to close its borders for a week – “we’re having a party and you’re not invited!”.

When I eventually dragged myself away from the comradeship in Bishkek the weather was decidedly on the turn, from late summer heat in Bishkek, via autumnal colours along the northern shore of Lake Issy Kul and the Karkara valley, to heavy, wet snow on the Kazakh border at 2000m. In Kegen, Kazakhstan, I spent my first night since France in a tent covered in thick snow, prompting further speculation about how I would cope with the weather in Tibet, and making me very glad that I had managed to track down some winter shoes, thermals and mittens in Bishkek. But it was a short lived cold snap that soon gave way to the arid climate of Western China. At the Kazakh border the guards plied me with bread and bags of sweets left over from their national day celebrations a couple of days before. A couple of days later, the Chinese border was pretty uneventful but for having to cycle 8km round a piece of no-man’s-land no wider than 200m, the customs building constantly in view on the wrong side of a high metal fence – an early precursor of things to come.

Leaving Khorgos I set out to tackle the 2000m climb over the Borohoro mountains, a spur of the immense Tien Shan mountain system. The road was effectively a motorway, but through this part of the country slower vehicles and livestock are allowed on the hard shoulder. I knew I was in for something interesting when I spotted on the map that the road appeared to do a loop the loop, and indeed this turned out to be my first sighting of Chinese mega-engineering. Two thirds of the way up the pass a suspension bridge towered 200m or so above the valley road, which itself curved inexorably rightwards, eventually disappearing into the mountain for through 3km tunnel before disgorging onto the suspension bridge at right angles to the road below. Spectacular.

Once clear of the mountains the road descended gradually to my first Chinese staging post, Urumqi, Xinjiang province’s main hub; a city further from the sea than any other in the world. I knew that with around 5700km separating my entry and exit points in China I had my work cut out for me to cover the distance within the 30 day visa plus one renewal that I could count on. I resolved not to hang around in Xinjiang, partly to allow more time later on in the more challenging terrain in the south, but also because, frankly, Xinjiang is pretty dull cycling. Given my schedule, the only sensible route was the G33 motorway via Urumqi, the Turpan Depression, through the southern Gobi desert to Dunhuang in Gansu Province. Electricity pylons, a 2m high metal fence and armco crash barrier were my constant companions for around 1400 tedious kilometres, with occasional interest from local agriculture.

Since the highway bypassed towns and cities, during my first ten days in the country most of my encounters with Chinese people were at the service stations where I stopped to resupply. In China I was evidently much more conspicuous than in other Central Asian countries, and usually drew a crowd of staring but always friendly locals whether I was on or off the bike. Few Westerners (‘big noses’) make the trip to deepest Xinjiang, not surprising really as until recently even mentioning the province in your visa application was a no-no, due to violent conflicts between the Beijing government and the Uyghur separatist movement there. Every petrol station and shopping precinct that I visited in Xinjiang had a visible police presence and I passed regular police checkpoints on the motorway, although I was only stopped and asked to show my passport once in China – ironically in Gansu rather than the more heavily controlled provinces of Xinjiang and Qinghai.

Actually that’s not strictly true. On the day I made a big push to reach Urumqi, just over 200km away, and after riding the G33 highway for five days already, I was brought to a stop on the hard shoulder by two police cars. The officers were courteous and amiable, but not at all happy about me being on this road, for safety reasons they claimed, and insisted that I leave at the next exit. Despite my dismay at being deflected this late in the day, I had no option but to accept the police escort, complete with flashing lights, for 20km through the neighbouring city of Changji, where, having removed me from a four lane highway with a wide shoulder separated from the traffic by a rumble strip, they deposited me on a busy, debris-strewn, eight lane highway with no hard shoulder, and cheerily waved me on my way to Urumqi. Akin to riding on the M60 Manchester orbital road at rush hour during roadworks, this was about twenty times more dangerous, but, unexpectedly 10km more direct, than the main G33 highway that I had intended to take. Manfully I slogged onwards through the increasingly dense air pollution past the city limits of Urumqi, bewildering in its extent and modernity after being out in the desert for a week, although at three million people, Urumqi is not a big city by Chinese standards. As I zoomed into the city centre on high level expressways alongside silent electric bikes, busses and taxis, clouds of steam billowing from street-level vents up to the miles of neon signs suspended on every vertical surface, I felt like I had arrived on the set of Bladerunner.

Pitching up late and pretty done in at a hostel in the heart of the city, I managed to blag a sofa to sleep on in the common room as the place was full to capacity due to the national holidays. A companionable day off ensued, sharing travel stories with other cyclists and travellers in the hostel and raiding the Carrefour supermarket for supplies for the next desert section. But I got precious little rest as the hostel was a noisy, shabby and badly run place (with a surprising number of mosquitoes considering the time of year and northerly latitude). As is frequently the case when I return to ‘civilisation’, I left feeling Urumqi more depleted than I arrived, but glad to have met some fellow travellers during this long and otherwise empty stretch, particularly Min, Jo and Ki, three Korean cyclists heading west, from whom I learned some useful Chinese phrases.

After Urumqi the days become a blur in my mind, with little to differentiate one from the next. My mission was simply to get through this stony wilderness as efficiently as possible without going completely loopy with the ‘thousand-yard stare’. The ever-present fences provided no real impediment to camping in the desert, as every couple of kilometres there would be a breach of some kind. I am unsure what the point of the fence was, as there was no livestock to keep off the road, and no incentive for anyone to venture into the featureless wilderness beyond. My best guess is that the fence marked the boundary of land owned by the national utility companies, but the expense and embodied energy in so many hundreds of thousands of kilometres of metal for such a trivial purpose beggars belief.

By the time I reached Dunhuang in Gansu province I realised that I was actually several days up on schedule; too late did I recall a friend’s pithy observation during the early hours of my Bob Graham Round run a couple of years ago, ‘time in hand at this stage is an illusion’ (for maximum emphasis you need to pronounce it with a laconic Geordie accent: ‘ill-uuuu-sion’. Funny the things you remember as the isolation grips you). As I couldn’t apply for a visa renewal in Golmud, only 500km south, for another week, I chilled out for a few days in the Silk Road oasis city of Dunhuang, wandering the nightmarket, checking out the impressively mountainous sand dunes that form the backdrop to the city, and sampling the horrors of Chinese beer and whiskey.

In Dunhuang I also experienced for the first time the stonewalling treatment that I had heard can be a problem when trying to interact with locals who don’t want to ‘lose face’ for not speaking English. On this occasion it was a market trader who refused to sell to me despite my approaching with a friendly greeting in Chinese. He got his bag of bread rolls thrown back at him for his troubles, and perhaps in future he’ll think twice before refusing food to a cyclist with low blood sugar. This and one or two other minor incidents notwithstanding, I am relieved to report that unwillingness to engage was very rare in China. On the contrary, I was often the beneficiary of unsolicited assistance from passersby when struggling to make my requests understood in hotels and shops. In Dunhuang a young Chinese journalist who was at the check-in desk when I arrived negotiated a better room rate for me, but not before he’d shown me his own spacious room and offered me the spare bed for free. Elsewhere, people generously escorted me round towns and brokered acceptable prices at guesthouse after guesthouse, hunting out places that would have been impossible for me to find unassisted.

In Golmud the hotel that had been recommended to me refused to take foreign guests. Thinking that they had surely misunderstood I persisted – I could scarcely believe that such a basically racist policy could even be legal in the enlightened twenty-first century – but the young guy behind the desk kept coming back with ‘no service for foreigners’, albeit in an apologetic manner that made it clear that he was not fobbing me off out of personal prejudice. After twenty minutes of this stalemate, a gentleman calling himself Mr Li appeared and offered to find me a more suitable hotel. We tried another five before we arrived at one that was licensed to accept foreign guests at a price affordable to me. Since hotel registration is a precondition of a visa renewal application, I was unable to avail myself of the much cheaper unofficial, unlicensed hostels that other cycle tourists had managed to doss down in. A quick shower and shave later I was down the PSB post haste and all set for a fast turnaround on the visa renewal next morning. Unfortunately the new visa began from the date of issue, not consecutively, meaning that I effectively lost a precious seven days off my existing visa. In Dunhuang I had deliberated back and forth about my prospects for cycling the whole way across China, but deferred the final decision about whether to go for it until I actually had the visa renewal stamped in my passport. More importantly, my prospects of an end to end run would be determined by whether I coud pass through the police checkpoint 35km south of Golmud, where I knew other cyclists had been turned back and sent on a long detour, usually by bus to Xining. Although I wanted to follow the G109 road south for only 100km or so past the roadblock over the Kunlun mountains before turning east into the Qinghai side of the Tibetan Plateau, it is the main route to Lhasa in the heavily controlled Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), all of which is closed to foreigners unless accompanied at all times by an expensive state-sanctioned guide.

To improve my chances at the police checkpoint I had prepared a map with my intended route through Qinghai province clearly highlighted, had a magic letter translated into Chinese that explained my trip and was ready to swear on the mani stone that I wouldn’t attempt to enter the TAR. My friend Henk had previously persuaded the police that he should be allowed to continue by ‘swearing’ that he would not go to Tibet; on the internet forums and blogs, others had not been so lucky, but at least I knew that in principle it was possible to sweet talk my way through. As I approached the roadblock late on a Friday afternoon I found a long queue of trucks waiting to be checked through. Instinctively I proceeded up the righthand side of the trucks, casually winding my way to the barrier in the dusty margins of the road, all the while expecting an unseen guard to call me to a halt. As I neared the barrier itself I drew alongside the frontmost truck and slowed to a crawl, wondering what to do next. At this point I was hidden by the truck from the view of the kiosk in the middle of the road, but I was in plain sight of the glass-fronted building on the right of the road, where truck drivers milled around waiting to present their papers to officers behind a counter that faced out directly towards me. I was sure to be seen now, so I steeled myself for the inevitable protestations and negotiations, but kept the bike rolling ever so slowly forward. Fortune clearly favours the brave, for just as I was almost abreast of the barrier itself, where I would have been exposed for sure, the leading truck started its engine, the barrier swung skywards and the truck lumbered forth with me keeping pace beside it. I could hardly believe my luck; still I expected to hear a shout, a dog bark or some kind of commotion, but heard only grumbling engines receding behind me. I sauntered along for a few hundred metres, breathing ever easier, before pulling into a petrol station for a celebratory can of coke.

Before me the Kunlun mountains brooded on the horizon, the road climbing to 4767m, the highest point of my trip so far. Physical acclimatisation to altitude lasts for only a few weeks, so I had lost all the benefit from being high up in the Pamirs earlier in the year. In any case, speed was impossible with the awful headwind that poured down the valleys from the Tibetan plateau. The gradients were gentle, but with the downside that trucks were able to motor along too fast for any ‘trucksurfing’. All along the G109 road the Chinese army was out in force moving hundreds of tanks, heavy artillery and armoured personnel carriers in convoy out of Tibet. Across the valley from one of the town-sized army encampments I camped twenty metres from a railway line, as I have done many times, reckoning that a few trains make a racket when they pass, but not nearly so much as constant road noise. How wrong I was. This single track railway conveyed heavy trains both into and out of Tibet throughout the night, every one sounding like the coming of the apocalypse, shaking the ground beneath my tent until I was sure I must have somehow ended up on the tracks themselves. So it goes.

The sandy hills of northern Qinghai gradually gave way to snowy scarps and peaks. As I topped out on the Kunlun Pass I kitted up for the descent just as the weather turned to sleet, slamming me with a freezing wet crosswind. The Tibetan plateau was doing its utmost to repel me, but I forced the pedals round on the barely perceptible downgrade and after 30km or so I camped at 4600m, although scarcely sheltered from the snowstorm. Never have I been so glad to get the tent up, spark up the stove and bed down in my two sleeping bags – this was as cold as I’ve ever been on this trip. The morning dawned clear and calm, and a new landscape opened up before me. The recently resurfaced S308 road to Yushu crosses a desolate, arid plateau riven with partly frozen streams, dotted with herds of yaks, lemmings dashing from hole to hole. For a whole day I saw only a handful of man made structures bar the the occasional telecommunications masts. My pulse quickened as I approached the first village on the plateau. Qinghai-Tibet is notorious for its ferocious dogs and strategies to deal with them are a perennial topic amongst touring cyclists (see also: bowel movements, equipment choice, visas). Many cyclists carry a pocketful of pebbles deter attacks from these frightful dreadlocked mastifs, and I scooped up a handful of stones as a precaution when I spotted the first couple of frisky-looking canine sentries. I am not a dog person; my first ever bicycle ride as a toddler ended abruptly I collided with a golden retriever, which proceeded to go mental, possibly scarring me mentally too. Over the years friends’ dogs have gradually rehabilitated me to mutual tolerance and sometimes even respect, but these Tibetan mutts had something of the Cerberus about them and I wasn’t expecting to make friends today. Recalling the canine psychology lessons I received from Eric in Baku, I went in on the offensive, riding straight towards the brutes and hailed them in as domineering a voice as I could muster. For some reason, out of nowhere, I found myself channeling the booming bombast of Ian Paisley, the late Northern Irish fire and brimstone merchant: “I’ve feckin seen you! Sit down (pron: doyn) and shut up!!!”. To my astonishment and immense relief it worked a charm. The dogs stopped in their tracks, barking their heads off but advancing no further. Time after time I deployed the Paisley heckle with the same results, so that I actually came to relish these encounters. Once or twice a couple of dogs got in under the radar and gave serious chase, but by stopping and yelling, baring my teeth and lobbing a few stones I was able to extricate myself even from these adrenaline spiked confrontations.

Across the plateau my only human interaction consisted in trying to obtain vegetarain fodder once or twice a day in the occasional villages. My company was essentially of yaks, yak herders, foxes, lemmings and deer. A profound solitude prevailed. On the third morning above 4000m I awoke feeling like I had been hit in the back of the head with a cricket bat. Morning and early afternoon were a write-off as this mother of all headaches (and I have a fair amount of experience in this department) was utterly refractory to all analgesics in my first aid kit, even strong coffee didn’t touch it. Since I had eaten well and drank plently of water the night before I was pretty sure that this was altitude related, despite having camped higher on the previous two nights. I decided to take the day off since I had a great spot with a view from my tent of the mountains, and was able to collect more water from the river, although keeping it in liquid form was to prove difficult from this point onwards (ominously, the river froze in many places overnight, the temperature somewhere down below minus 15 Centigrade – in fact everything outside my sleeping bag froze solid most nights, toothpaste, wet wipes, water filter). I lay in my sleeping bag reading Heinrich Harrer’s account of his time in Tibet and a collection of the Dalai Lama’s essays, and reflected on the cultural violence done to this once proudly independent nation.

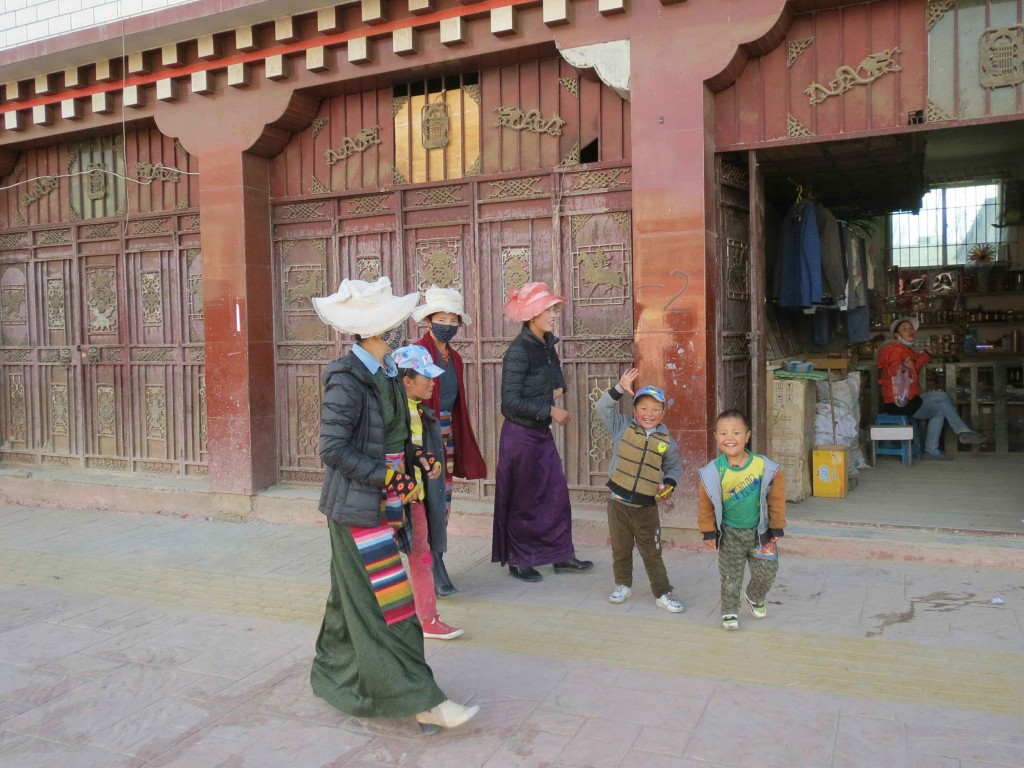

All along the road to Yushu I was blessed with strong tailwinds, enabling me to cover 100 to 120km a day, despite two more high passes scraping 4800m. As I finally descended into Yushu City well after dark, half frozen from the long descent off the high plateau, I discovered that even fairly decent looking hotels lack central heating out here in the wildwest of China. As always in China, my bed was comically hard, more like a low tabe with a duvet on it, and I wore my down jacket in the room while the tiny infrared bathroom ceiling heater radiated pathetically. Yushu was levelled by an earthquake only five years ago, the Chinese government poured concrete at a prodigious rate and fully rebuilt the city in the meantime. Every tiny shop has a music speaker outside blaring discordant pop music at full blast; no banks accept western cards; a strange city indeed. In a restaurant on my second evening in town the staff fawned over me, the big nose freak who had fetched up in their manor. They spoke hardly a word of English so I showed them my magic letter and won their goggle-eyed adoration, and they asked me how to pronounce the names of the expensive European wines destined for their wealthier customers (even in supermarkets wine is fantastically expensive in China). The two Chinese waiters then proceeded to walk around the restaurant for the rest of the evening practising saying ‘Bordeaux’ over and over, mimicking my Lancashire accent, ‘bore-dough’. My own efforts at Chinese were probably equally comical to them; I always enjoyed throwing out my stock phrase ‘wo shi ying guo ren’ (I am from England!) with the irrepressible flourish of Manuel from Fawlty Towers.

In Yushu I re-evaluated my chances of cycling out of China before my visa ran out in just over three weeks time. By all accounts that things were about to get a hell of a lot hillier and rougher in Sichuan and northern Yunnan provinces. Undeterred, I resolved to give it a try anyway, taking a route via the town of Shangri La, where I had heard the police were fairly cooperative in issuing visa extensions, and decided to try for the fabled second visa renewal. If I cycled 130km a day from Yushu to Litang, then 90km a day over the rough mountains to Shangri La, I would still have enough time to cycle out of the country if I was refused a longer stay. The first few days went pretty well although even on the good roads between Yushu and Litang I struggled to make the daily distances, generally ending up in the hole to the tune of 10km or so each day. Resolutely I ploughed on, trying desperately to keep the total mileage in prospect.

Just after Zhuqing I hit the start of a 4400m pass at dusk. In a quandry whether to keep going or find a place to bed down amongst the rubble and construction debris (a new tunnel was being bored through the mountain), I decided that to camp at the bottom before dark was effectively to give up on the end to end ride, so I pressed on up the loose, sandy switchbacks. Improbably, at this most inconvenient of moments, the hitherto tranquil road was beset by traffic, with several container lorries and four wheel drive trucks vying for space on the mountain road, with me usually squeezed off the road in the gathering gloom of dusk and dust. Barely halfway up when darkness properly fell, I fumbled in my handlebar bag for my lights and a snickers to get me to the top. Just as I snapped the rear light into place a juggernaut crawled round the bend below me on the wrong side of the road, so I scuttled off up the road to get out of its way as briskly as possible. At the next corner, a 4WD truck hurtled towards me and disappeared down the hill into the night. Cursing I reached into my bag for the snickers to restore my blood sugar and sense of optimism. My innards turned to ice when, sensing that there was far more room in there than there should be, I realised that my camera was not there, because… of course, shit! I had taken the camera out 200m back to get my lights out from underneath it and placed it on the front left pannier, as I have done many, many times before, to save it falling from the bar bag as I rummage about. I dropped the bike in a lay-by and ran pell mell back down the road to the point where I had stopped only moments before. Ahead in the pale dust my torch beam picked out a black shape that was obviously the neoprene case of my camera, which I thought would probably have survived the fall from pannier height. A few more steps closer and the black object appeared less distintly camera-shaped, but no there it was, in its case… I stooped and saw up close the neoprene case smeared with dirt and tyre tracks, and as I lifted it from the road my heart sank as I felt the crunch of glass, metal and pulverised plastic within. Hot tears of frustration and exhaustion pricked behind my eyes, and I bellowed a cathartic profanity to every Toyota Landcruiser in the world. Self pity engulfed me as I trudged disconsolately back to my bike, mixed with feeling ashamed at my foolish hubris in pushing so hard… for what purpose?

I strained to master my emotions and order my thoughts. I’m okay, the bike is okay, it’s only a poncy flippin camera, get a grip man and get moving off this bloody awful road. Cresting the pass would entail a descent just as rough as the climb but far more dangerous in the dark. I scoured the the hillside above the road and found a small flat area amongst the rubble left by the construction crews and proceeded to haul the bike and panniers up there as wet snow started to fall. By next morning my pragmatism was sufficiently restored by sleep, carbohydrate and caffeine to write the whole incident up to experience and I set about learning the lessons it offered. I still couldn’t bring myself to investigate the mangled camera body to find out if the SD memory card had survived. I set my sights on getting to Garze that night, the next big town in the region 120km away, where hopefully I could find another camera of some kind or other.

In Garze I was relieved to find the SD card with the last five days’ photos intact. Exhaustive hunting amongst the ramshackle shops of this wildwest I managed to find a basic point-and-shoot Canon Ixus 500 for around $100. But rooting it out and haggling took time, and I pedalled out late in the day under a metaphorical black cloud. Nothing felt right, my inner monologue a veritible tirade of whinging. My bike was heavy, my clothes were uncomfortable, my bum hurt. Recognising this nonsense for what it was I camped early when I spotted a good hideaway and cooked a proper feast. Drinking my coffee in the morning I listened to music on my earphones, the serendipitous chorus of the Byrds’ singing Bob Dylan’s Nothing was Delivered percolated into my brain: “nothing is better, nothing is best, take care of your health and get plenty of rest”, and it dawned what a fool’s errand I had got caught up in, flogging myself across this madhouse country for some futile goal of riding end to end. Perspective and a pedal-steel, sweet.

I saddled up feeling much more relaxed, soon stopping to chat with some lads on a motorbike. With a backward glance as I set off again I spotted the first fully laden touring cyclist I had seen in almost two months (Chinese tourers universally prefer front suspension mountain bikes and backpacks for the glass-smooth roads they ride). Enter MinHsiang from Taiwan, four months into his six month circuit of China and heading my way for the next couple of hundred kilometres. Both glad of the company, we teamed up for a few days and pottered along from village to village, Min introducing me to his concept of (indoor) camping, while I tried to get Min to eat more than just packet noodles. We parted just before Litang, Min bound for Chengdu to the east, while I sloped into town at dusk to find a hostel to recharge my physical and electrical batteries and do some laundry.

At the first place I spotted, Lucky’s Litang Inn, I received a friendly greeting in perfect English from an attractive, breathy-voiced Chinese woman in a pink fake fur coat, who told me that I could have a private room for 100 yuan or a dorm to myself for 25! In the hotel restaurant I loaded up on on fried rice and vegetables, usually a safe option. Two hours later I was running to the dorm’s wretched squat toilet as my body violently rejected whatever foulness lurked in the hotel’s kitchen. Squat toilets are truly detestable things when you have an affliction wreaking messy havoc at both ends of your alimentary tract. After such a horrendous night, I could barely move the next day, by evening just about managing to eat a banana and snickers. A full day later I managed to get another couple of bananas down and slowly packed up my things. The hostel woman was compassionate and expressed concern, although bizarrely in the form of offering me strong alcohol to drink at 9am after I had spent over a day without proper food! At least she did not ask for payment for the extra night, apparently accepting that her kitchen was probably responsible for my bedridden state. I decided not to comment on the perversely innappropriate name of the establishment.

Tentatively I headed up the road towards the mountains on the border between Sichuan and Yunnan. I had been warned that on this section things get much tougher, so I had by now given up all hope of an end to end ride without a second visa renewal in Shangri La. The naivete of my previous schedule was hammered home to me as I struggled to make even 60km a day in my enfeebled state from effectively fasting for two day, crawling over repeated 4000m plus passes. In an overpriced flophouse in Sangdui I cooked lentils in my room and contemplated the even higher passes to come, where I had been reliably informed that the road becomes “bad, let’s say very bad”. I read a timely email from my former riding buddy, clog-hopping Silk Road cyclist, Ritzo, commiserating about my scuppered schedule and reminding me that “it’s all in the mind”. The words resonated. Pressing on through this vast, over-regulated country, alway watching the clock and the calendar – China had really gotten under my skin. But here I was in the middle of all this beauty and wild nature, doing what I want to be doing. So why did I keep getting so worked up? Here and now boys. Here and now. Immediately the change in mindset paid dividends and I was able to enjoy the climbs as much as the descents. I passed through Tibetan villages in deep, green, forested valleys where the clear cold air was sweetened with the scent of pine needles, homely wafts of woodsmoke replacing the the tang of burning yak dung.

Deciding to take a leaf out of MinHsiang’s book, I called at the village police station in Shuiwa to enquire for a place to sleep. The only person in the building complex, Duyuin (an unfortunate name for a policeman, I thought), straight away offered me a bedroom of my own in the sleeping quarters, and while the local doctor and friends prepared food for us, Duyuin returned with two twelve packs of beer for me! Weak as water Snow beer, fortunately, so a few cans served to rehydrate rather than intoxicate.

Next morning I climbed the switchbacks out of Xangcheng, the road surface like broken bricks, and it took me a day and a half to cover 60km. But the payoff was immense; the steep mountains Dolomitic in profile, pine forests heavy with old man’s beard lichens, tree-strewn limestone precipices glowing in otherworldly hues of blue and purple in the pre-dawn light. On my last night before the run into Shangri La, I spotted an abandoned wood shack at the roadside. I untied the USB-cable shackle on the door and peered into the gloom, spotting two sleeping platforms and a wood burning stove, and from the general messy ambience it had obviously been abandoned for the winter. Finding a few logs remaining in the woodpile and a source of fresh water across the road sealed the deal – this was a great place to stay, I could make an early start in the morning as I wouldn’t have to wait for the sun to rise over the mountains to dry my sleeping bags and tent. The mountain pass was so quiet, no vehicle had passed for almost an hour, so I didn’t hesitate to get a fire going and cooked a great meal, getting my head down around 10pm. Sometime after midnight I was roused by the sound of squealing brakes and the rumble of a truck engine right outside the front door. Suddenly wide awake, I rolled over to see if there was still light coming from the fire in the stove. Only a few glowing embers, but I could see a faint thread of smoke escaping the stovepipe at the back of the hut. On such a clear night it was bound to be seen, or certainly smelt. Then another squeal of brakes and another engine. Music blaring from the cab. Voices shouting in Chinese. My heart now beating twenty to the dozen, I felt like Goldilocks when the three bears came home. Another truck, daddy bear presumably, and finally a fourth. Shit!! They must use this as an overnight stop off or something. I was sure the door would creak and the heavy rock I’d placed behind it start to scratch across the boards at any moment. Splashing and gurgling noises. One engine still running. Loud conversations, right outside the hut. What the hell are they doing? More watery splashes. Then I twigged. In China trucks spray water onto their brake discs to prevent overheating on the interminable descents. Here at the top of the 4000m+ pass the drivers were filling up their brake cooling tanks. Eventually, one by one the engines started up again, followed by the crunching of gravel under heavy wheels and I was on my own again, a forty-five minute eternity after I awoke.

A fitful night’s sleep later I bashed out the remaining 80km to Shangri La. Here I would find out whether my Chinese adventure was about to come to an abrupt end, or if I would be granted a stay of eviction. Strangely I had ceased to care about the outcome, I was much more excited to have reached Shangri La while Ritzo was still there. As I blundered around the rabbit warren-like ‘old town’, searching in vain to find the hostel he was staying at, I heard the unmistakable klomp of wood on cobblestone behind me. It was great to see him again, although with his swarthy tan and Tibetan pig-tailed hat I thought for a moment he had gone native. (It turned out this was exactly what he was intending to do, having secured a job in town for the next month – he had a three month visa from Tehran, plus one month extension).

Next morning after a thorough wash and brush up I presented myself at the PSB. The moment of truth had arrived. The immigration officer calmly listened to my entreaties and gave an unequivocal ‘no’. Since last year only one renewal is allowed on my type of visa they said, so I must leave the country immediately. This struck me as a touch melodramatic as I still had four days remaining, and on further enquiry I ascertained that I could take a 12 hour bus to Kunming and then another to the border with Laos so there was no need to panic. Instead, I bought a ticket for the bus departing next morning and proceeded to help Ritzo settle into his new job as bartender in the Raven bar. Staggering home after 2am, I found that the idiot guesthouse owner had put someone else in the room I had paid for as a private room, despite me leaving the door padlocked and my all stuff lying about on the two beds. The poor Chinese motorcyclist who I disturbed didn’t know what was going on as I drunkenly moved my kit into one of the six unoccupied neighbouring rooms.

Shangri La did not live up to its literary namesake in Hilton’s Lost Horizon as a haven of tranquility and quiet meditation. The town, formerly Zhongdian (also known as Deqen, Jiantang, Gyalthang and god knows what else) was only renamed Shangri La around a decade ago after a bidding competition amongst several candidate towns, but why any town would want to associate itself with the frankly creepy, Hotel California-esque lamasery of Hilton’s novel escapes me. Perversely it was from this place, named for a mountain fastness that you can never leave, that I was now being booted out of China. From my airconditioned coach I watched the pine forests turn to rice paddies and jungle, perfectly soundtracked by hangover-friendly Asian and Gypsy grooves courtesy of my friend Elina, as I barrelled towards the tropics. In Kunming I discovered there was a nightbus departing the following evening, so spent a day cruising around the city and obtaining a full chain set and bottom bracket overhaul from the fantastically helpful lads in Merida cycles. Next morning, fifty-two days after entering the country in the barren northwestern extremity, I arrived amongst the banana trees and bougainvillea at the Chinese-Laos border with all of twelve hours to spare on my visa.

Eight weeks ago, China was an enigma. It still was. In the interim I had visited some of the lesser travelled places in Asia, seen life in the arid wastes of the Gobi desert and the Tibet-Qinghai plateau, amongst the world’s most inhospitable places, travelled from one of the lowest points on Earth in the Turpan Basin at -150m to knock on the ‘roof of the world’ at 4800m. But I got little sense of what makes the country tick. The mega-cities of the east – the wellsprings of China’s political and economic ascendancy – will remain terra incognita for me. Truth be told I was glad to be leaving China, and although I am grateful to have witnessed life in the wild west of this heterogenous empire-like nation, I have never felt so alien in my life. Local customs and interactions jarred with my ingrained Western sensibilities in every town I stopped. No amount of self-awareness and reminding myself that “we’re not in Kansas any more” could make the violent expectorations that punctuate every night and day any less revolting, make the yelling and banging on hotel doors at 4am any less inconsiderate, the default 100db conversational volume any less alarming, the incessant horn honking any less obnoxious, the widespread no-foreigner hotel policy any less offensive, or make the constant staring any less tedious. Actually I quickly got used to the staring, but the rest of it constantly frayed at my nerves. The fact that it’s all perfectly normal behaviour in these parts, that I am the misfit here, offered scant consolation at the time. Such peevishness aside, with the benefit of a couple of months hindsight, I am glad to have I spent as long as possible in the country, grateful for the lessons it taught me – more about myself than itself – and thankful for the memories of cycling in the Tibetan region and the mountains of Sichuan, memories that will last a lifetime.