Listening to the rice grow

“The Vietnamese plant the rice, the Cambodians watch it grown and the Lao listen to it grow.”

French Colonial saying.

Crossing the border from China into Laos, the contrast in culture couldn’t have been more stark. After China, where social interactions are generally loud, expressive affairs, Laos people seemed to conduct themselves with an amiable diffidence. More to the point, in Laos people drive slowly and don’t honk the horn constantly. I was still slightly disorientated by my bus journey from Shangri La to the border; the landscape, climate and culture had changed much more quickly than I’m used to, having leapfrogged from wearing a fur hat and down jacket in the mountains of northern Yunnan, to the steamy, lush forests of the tropics. As I adjusted to the heat and humidity, my ears tuned into the musicality of the Laos language; the melodious greeting ‘sabaidee’ emanating from every front porch along with lilting, calypso-like dance music. Around the villages, streams of kids in crisp white shirts cycled to and from school, parasols in hand. Elephants bimbled along the road, their drivers perched on makeshift howdahs. The sun shone and the beer was cold. If a country can be summarised in two words, Laos was ‘obladi oblada’. After the craziness of China, this was just the tonic I needed.

Camping on the edge of scrub jungle was tentative at first, as Laos is riddled with unexploded ordnance (UXO) from the second French Indochina war (factoid alert: historically Laos is the most bombed country per capita in the world). I wound my way over a series of low hills in the northern fringes of the country to follow the Mekong River south to Luang Prabang, the old royal capital. The aromatic scent of sandalwood was never far away, as the locals made charcoal from timber, and orange and pink-robed young Buddhist monks padded along the streets. The relaxed tempo of Laos life was starting to work its magic, and I looked forward to a break of maybe four or five days, wandering the cafes and temples of this colourful, chilled out town. My search for the cheapest hostel in town led me to Spicy Laos, an odd place to be sure, but where to my delight I discovered a few other cyclists – Marc from Germany, whom I’d bumped into three months before at the roadside in Kyrgyzstan; and Francis, Vincent and Chris, three Belgians whom I’d already had a drink with on my first night in Laos. Days sightseeing in and around town segued pleasantly into evenings drinking and talking late into the night with the cycling contingent, along with Tan (an adventurous traveler from Chengdu, China who has a story for every occasion!) and later Mike (formerly of Bridport and Manchester). Luang Prabang’s 11pm curfew meant that the only late night option was a Chinese run ten-pin bowling alley a few kilometres out of town, so the phrase ‘let’s go bowling’ was often heard in Spicy Laos. This, combined with long afternoons sipping ‘oat-sodas’ (rice in the case of Beer Lao) and swapping country rock music with John, mustachioed expat-American sage of Luang Prabang, meant that I was soon in full-on Dude mode.

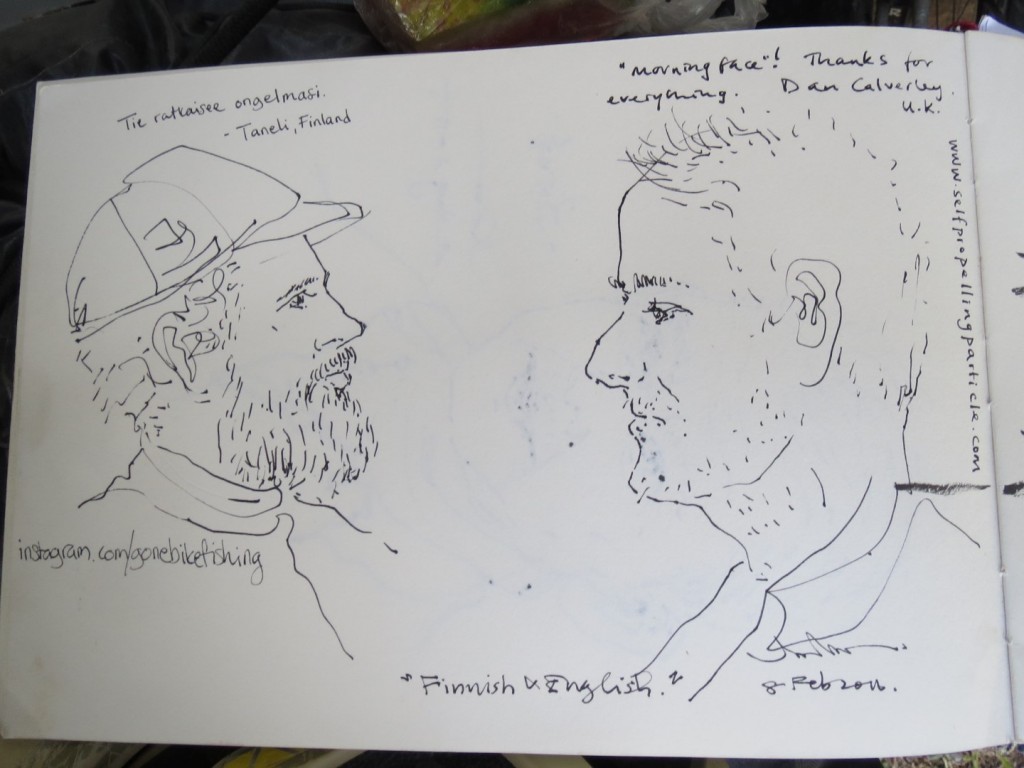

Throughout my time in Central Asia and China I had stayed in touch with fly-fishing Taneli, who was still trailing me by three weeks or so after his wild-goose chase in Iran (the Turkmenistan embassy stopped issuing visas when he arrived, so he was forced to backtrack to Baku for the Caspian Sea boat, then followed my tracks along the central Silk Road). Planning to rendez vous with him in northern Vietnam, I bided my time while he slogged across Sichuan. My five-day respite in Luang Prabang slipped to a week, then to ten days… an ever changing cast of characters passing through the hostel. My bike leaned dejected against a staircase at the back of the hostel, cobwebs blooming on the handlebars and rust starting to speckle the chain as an unseasonal mini-monsoon deluged the town for two days. I drank rum, played cards, visited the UXO centre, twiddled my thumbs. Eventually, twelve days after the reverse culture shock of arriving in this pretty town swarming with Western tourists, I somehow managed to build up a sufficient head of steam to cycle south to the limestone landscapes of Central Laos.

I was aware that the road from Luang Prabang to Vang Vieng crossed a few 2000m+ mountains, but it looked innocuous enough on the map, not too many squiggles and switchbacks I thought, so probably no great shakes. In fact, its relative straightness is accounted for by its stupendous steepness. With an average gradient over 10% for over 50km, this scenic stretch was the longest consistently steep hill of my life. My early hutzpah faded fast as the steeply banked corners bludgeoned my legs and I was reduced to a crawl, zigzagging across the full width of the road in my lowest gear for 20km (22-34 for you gear fetishists). I was relieved to find that Vang Vieng’s reputation for hedonism was somewhat overstated, the worst excesses of drink and drugs having been curbed lately after several deaths involving ‘tubing accidents’ (the favoured tourist activity there is to float down the Nam Song river in a tractor inner tube while off your face on free shots, and the rest, from the riverside bars). In the event the natural beauty of the caves and water holes of the surrounding area made for a pleasantly relaxing interlude before I turned the bike around and headed north to Hanoi. The less said about the perqs of free whiskey in my hostel the better.

Glad to be moving again, I crossed the prehistoric Plain of Jars into the hill forests that rise up along the Laos-Vietnam border. For three or four days I toiled up inclines even steeper than on the Vang Vieng run. This little travelled part of the country was a world away from the tourist crowds in the honeypot towns of the Mekong valley. In ever more remote hill-top villages of rickety wooden shacks thatched with palm leaves people stopped and called ‘sabaidee’ as I trundled through. Groups of flip-flop wearing young men passed by on wheezing-engined scooters, hunting rifles & jungle knives slung over their shoulders. Rather discomfittingly, on two occasions I spotted an AK-47 casually draped across someone’s back – the obviously hunt some pretty big game in these parts. A cold, damp front blew through from the east and I found myself digging out my winter gloves and long trousers from the bottom of my pannier.

Across the border into Vietnam, the asphalt abruptly deteriorated into a road-building site and I choked and squinted my way through the ochreous dust churned up by the endless stream of construction lorries for almost 100km. With the aural assault of impatient traffic, horn honking, and repeated near misses by homicidal bus drivers and fuel tankers, Vietnam and I were getting off to a bad start, but I tried to reserve judgement until the riding conditions improved. They didn’t. The three-day ride from the border to Hanoi were easily the most unpleasant since the Uzbek desert.

Camping was also proving to be a headache in Vietnam. Exhausted on my first night in the country I tried to get away from the development along the main road and into the surrounding countryside. What luck, I found a riverside clearing in the bamboo that looked like an ideal campsite. I was about to start pitching my tent when a local chap whom I had passed on the dirt path into the woods turned up and mimed that I should leave. He wasn’t threatening or even very good at mime, but his voice drew the attention of two passing women and a younger man who took it upon themselves to join in. It was all perfectly good-natured and I worked hard at charming them and getting them to understand that I posed no threat and was in no danger myself by camping here. After ten minutes of mimes and smiles I had managed to win them over and the four of them started to help me clear the ground to place my tent. Unfortunately, at this point several more Vietnamese men arrived, because the first halfwit had been busy on his mobile phone when he initially arrived. Despite having the consent of the first group, now the second wave needed to be convinced afresh. Between my entreaties and some words from the women I could see they were starting to come round when a third delegation of local busybodies showed up and jumped on the eviction bandwagon. By now outnumbered eleven to one, I was running out of steam. When some officious types actually started to pick up my things I realised I had no option but to withdraw. In a huff I repacked the bike, sulkily refusing the assistance of a couple of the younger guys who seemed most sympathetic to my cause. Apparently embarrassed by my petulance, or perhaps because of the fuss they had made over nothing, the gathered crowd drifted away to their scooters in ones and twos and I found myself alone again in the clearing. I sat, smoked and considered my options. I was exhausted from the awful day’s ride and ravenously hungry. It was already dark now and my prospects for finding another campsite unobserved were very slim. Would the local militia return to check that I had cleared off? I decided that it didn’t matter; until I ate some proper food I wasn’t fit for anything, so I unpacked the bike again, put up the tent and got the stove on. Two hours later I was in my sleeping bag reading when a torch beam flashed through the flysheet, accompanied by the sound of dead leaves crunching underfoot. With a sigh I threw on some clothes and went out to face the music. But this was not one of the last mob of interferers. I was greeted by a sinewy fellow of indeterminate age (between 30 and 60, it was impossible to tell), who apparently lived in one of the shacks a few hundred metres further into the bamboo jungle. His demeanor was kindly and it soon emerged that he wanted me to come and stay in his house. Through gestures I communicated that I was okay here, very tired now, and that if he didn’t mind I’d just sleep where I was. After friendly handshakes he left me in peace and I settled down to a heavy slumber, undisturbed the whole night.

An uneventful but tiresome two days later I found myself at the periphery of Hanoi at 5pm, just as the tidal wave of rush hour reached its peak. Jockeying and jostling for position amongst the hundreds of thousands of scooter commuters, I was absorbed into the unstoppable shoal, one self-propelling particle among legion. The two-wheeled torrent effortlessly bifurcated and coalesced, like quicksilver through a maze, as it permeated the intricate matrix of Hanoi’s old town. This was the Asia of my mind’s eye, a city whose pulsing heartbeat you could feel, its vascular streets coursing with energy day and night. Thoroughfares barely wide enough to drive a car down were further constricted by encroaching food stalls with their flotillas of pixie-sized plastic tables and chairs; toothless women wearing conical bamboo hats stirred steaming cauldrons of noodles and fish broth on every corner; tinny, discordant vehicle horns vied for acoustic supremacy with equally tinny, discordant pop music from the open fronted shops, which in turn, at certain times of day, had to compete with patriotic, martial-sounding music from lamppost-mounted speakers.

My haven in this seething, humid, human tumult was to be Hanoi Rocks hostel, where Taneli had already installed himself, having been turned away by three or four others that would not accept bicycles. In this hostel the common space consisted of a bar and nightclub that occupied the ground floor, with free beer every night catering for young backpackers in pre-Christmas party spirit. No matter – an exuberant Anglo-Finnish reunion demands drinks aplenty. But the ensuing hangover was merciless and for three days we festered in that Hanoi pit of hell before finally, on Christmas day, we escaped the depravity and pedalled to freedom at the coast. Instead of Christmas dinner in a coastal paradise as we had promised ourselves, it was spent hiding from the rain in a roadside motel, albeit with French wine and cheese and other comforts furnished by Hanoi’s best supermarket. The promised charm of Cat Ba island never materialised, its coastline a derelict building site, abandoned when the Chinese tourist trade dried up in the early 2000s.

On a grey morning in late December, we surveyed the sea stacks of Halong Bay from our ferry and decided to cut our losses with northern Vietnam, and I resolved (not for the first time) to place less store by guidebook recommendations. We planned a route that looked to offer good cycling back to Laos and thence to Cambodia and the Gulf of Thailand, seeking hills and avoiding the heavily developed coastal areas where camping was almost impossible between the rice paddies and industrial activities. At a homestay-hostel near Ninh Binh the hosts laid on a ‘New Year’s Eve’ party for us, but switched off the music and kicked our small group of vagabond travellers out of the venue before 11pm. All along the busy roads back to the hills the vibe of Vietnam grated. The locals were friendly enough, but loud and abrupt; ‘hellos’ were shouted like harangues. Dogs were belligerent (so would you be if you were on the menu everywhere). The food was as grim as ever in the backwaters of the border country – instant noodles in grey watery soup, with a couple of fried eggs thrown in if we were lucky – but it was a relief to be back in the hill country where people were more curious and less strident. For four or five nights we camped amongst bamboo and tropical woodland, the strangely comforting background susurration of the cloud forest occasionally pierced by shrieks of unfathomable origin – whether bird, frog, insect or monkey I never could decide. Fireflies traced phosphorescent arcs around our tents and freshwater crabs scuttled for cover as we bathed in streams.

On our last night camping in Vietnam the forest sent individual emissaries to our tents, surely a sign of acceptance. For me, a bright green frog that landed in my tent porch as I ate my pasta dinner from the pan. Momentarily stunned by the amphibian’s boldness I sat transfixed. Quick as thought, the frog leapt into my dinner, inches from my face, and I instinctively threw down the pan (reports vary as to whether a girlish shriek was heard in the vicinity), spilling half the spaghetti in the dirt while the frog bounded away with a mocking croak. For Taneli, it was his first encounter with a leech, which to his credit he bore stoically, once I had read him the relevant sections from the medical and survival books on my Kindle.

In the morning we returned to Laos, Taneli going north to the limestone areas I had travelled previously, while I headed south to find a tranquil spot to catch up on writing. That spot was the town of Savannakhet, a sleepy, French colonial town on the Mekong. With not much to do but eat, sleep, drink and wander the cafes of this positively somnambulant burgh, Savannakhet worked a slow balmy charm and a week flew by, during which my first year on the road was marked in good company with Taneli, and fellow Brits Fiona, teaching English in town, and visiting cyclists Simon and Antony.

During the last six months I had been in email contact with Ben Smith, an old friend from my first post-grad job as a corporate wedger, headhunting sales staff for computer companies (hey, I was young…). Now living in Bangkok, Ben had generously offered to let me stay in his villa on Koh Mak island off the coast of Thailand near the Cambodian border. We planned to rendez vous there in a week’s time, so I said goodbye to Laos for the last time, crossed the Friendship Bridge over the Mekong into Thailand and hammered out the 700km to the coast via a side trip to the temples of Angkor in Cambodia. Angkor Wat was as beautiful in the evening glow as you may imagine, but, as the Angkor archeological park is Cambodia’s main tourist attraction, in a day spent sightseeing there I must have rubbed shoulders with half a million people. At least half of whom wanted me to stand aside so they could get a better selfie in front of some tree root or bas relief frieze or other. I know, I know, I wasn’t stuck in tourist traffic, I was tourist traffic, but being part of such a marauding horde of gawpers sat uneasily with me and I was glad to return to the road and spend my time and money in the places in between the major sights. In any case, the real gem of Cambodia is not the temples, but the gently jovial Cambodian people themselves. Get this. When I was paying for my hostel bed in Siem Reap at 5am (pre sunrise trip to Angkor), another guest was getting flustered about having lost his receipt. I carped that the hostel’s policy of ‘no receipt, no payment received’ was bollocks, they knew exactly who has paid, it’s on the computer. Instead of arguing back, the young Cambodian duty manager just smiled and started to sing in a beautiful, soaring falsetto. In an instant, early morning crabbiness evaporated and we all three started to laugh aloud. I can’t but think that this small incident is somehow emblematic of the Cambodian temperament – serene and good humoured despite having endured the most unimaginable horrors only a few generations ago.

Back in Thailand I was borne along smooth roads by a pleasantly cool tailwind that was causing all kinds of unseasonably cold weather further north and east. I wondered if I would recognise Ben after fourteen years of absence, and whether we would still have anything in common. Spotting his cheeky grin coming along the pier, I had the odd but satisfying feeling that we had spoken only last week, his voice so familiar as we reminisced on the speedboat to the island. Koh Mak is the laid-back neighbour of bigger, brasher Koh Chang; a low-key little island hideaway where people come for the pristine palm fringed beaches, and… well, to be truthful, there isn’t much else to Koh Mak. It’s all about cocktails, sea swims and sunsets. And not getting poleaxed by falling coconuts on the beach (a serious hazard). In Ben’s four bedroom, seven veranda villa with 50m tropical garden, I settled into some hardcore R&R, luxuriating in a soft kingsize bed, sprawling in chairs with a book and G&T, exploring the perimeter of the island by scooter and later, once Taneli caught up with me there, by kayak. But in this most comfortable of environments I started to feel the stultifying effects of three months of soft living catching up with me and my thoughts turned to plans for the rest of 2016. Mornings and afternoons were spent poring over guidebooks, maps and spreadsheets and a plan emerged that would take me to Nepal in time for the spring trekking season. Taneli’s route lay south to Indonesia and Australia, but first we both had business in Bangkok, so it was there that we headed directly.

By some miracle our bikes survived the rough crossing in the bow of the speedboat back to the mainland, demonstrating that Surly and Thorn bikes can withstand being dropped onto a boat deck from a height of two metres at least 500 times in fairly quick succession. Safely back on land, we team-time-trialled the undulating road to Bangkok, stopping en route to stay with Poei, resident meteorologist and talented artist at Chantaburi Horticultural Research Institute, and my first Warmshowers host since Baku seven months ago. In Bangkok, Ben and his girlfriend Nee had once again generously offered us a place to stay, this time at their home in a luxury condominium. Perhaps because of our disheveled appearance from two long hot days on the road and the previous night’s camp, the condo’s concierge took pity on us and collected our grubby panniers onto a trolley and conducted us via express lift to Ben’s salubrious 37th floor apartment. From this tranquil eyrie in the heart of the city were able to make short work of our various administrative tasks and kit replacement missions. Within three days I had scored a visa for Myanmar (Burma), bit the bullet buying a new Sony A5100 camera to replace the one that committed camera hara kiri in China, sold my Samsung tablet and keyboard, and bought a Windows laptop and new smartphone to replace the by now basically unusable Fairphone.

The essentials taken care of, the Himalaya was calling to me, and Bali to Taneli, so with hugs all round we went our separate ways, probably – I’m sad to say – for the last time on this trip. By heading east and (mostly) turning right I had now ended up facing north and west, back into the interior of the Asian continent, whereas Taneli has a more elegant, less meandering circumnavigation in mind. On the fast flat road north of Bangkok I enjoyed the feeling of speed, my swift progress facilitated by regular access to cheap ice coffee in the ubiquitous, air-conditioned 7-Eleven stores that lined the highways in Thailand. During these last few days in Thailand I was fortunate to see a more domestic, homely side of Thai life through very welcome stopovers with two wonderful Warmshowers hosts: Joe, an electronic engineer and local cycle club president near Ayuthaya, and Aod, human rights lawyer for IRC and avid bike rider at Mae Sot near the Burmese border. Thailand, it transpires, has more in common with British culture than I ever imagined. For one thing, Thailand is the first country I have visited since Italy that has a visible cycling culture, where people ride bikes for sport and pleasure; with Joe and friends I shared the lanes around the Ayuthaya area with scores of local club riders out for their Sunday spin and I got my first ride on a fixie on Aod’s minimalist chrome town-bike. There is also a politeness and reserve that I did not expect to find in Thailand, my preconceptions of its tourist-baiting, brazen character being considerably wide of the mark.

My three-month sojourn in South East Asia at an end, I totted up that of the ninety-two days since I’d left China I had been off the bike for forty-one of them. During that time I had kicked back in fine style, gorging on falang food at every opportunity, regaining the weight I had lost in Central Asia and China. Through reading and listening to other travelers I renewed my hunger for new adventure in parts unknown, away from the comfortable, sterile bubble of 7-Elevens. Perhaps because of the unsettling glimpses into mass tourism, my easy life in the lowlands of S.E. Asia has served its purpose to refresh my focus and vigour. Now, with eager anticipation, I look north to Burma, Assam and Sikkim, to the Nepalese Himalaya and to the mountain passes of Ladakh and Kashmir. I still have unfinished business with the high ground of Asia.

6 March 2016 @ 07:25

Really enjoyed reading this. You write very well 🙂

1 March 2016 @ 06:21

Great read as ever! Fascinating to hear your take on places I’ve been t. We loved Laos, spent longer than planned in Luang Prabang. I recognise that cave in Vang Vieng! Sounds like Vang Virng is nicer now than it was, full off teenage hedonists nursing hangovers and watching Friends reruns at the time.

Enjoy the himalaya. Can’t recommend the Everest base camp trek highly enough!

29 February 2016 @ 21:39

Wonderful as usual. Cannot believe that a whole year has passed by. Looking forward to your next installment. Love family Slade xxx