A rough, rough way to go

On the road for six months now, I have been gloriously free from daily and weekly time pressures. Visa constraints notwithstanding, my only real deadlines this year have been to cross the higher Asian mountain ranges before winter, and, ideally, to traverse the desert regions of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan before the hottest part of the summer. Still on target for the first and most important deadline, true to form I singularly failed to meet the second. Eastward progress so far has been something of a trade off between making the most of each day on the road, and the urge to press on through Europe, Turkey and the Caucasus in an effort to reach the arid expanses of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan before mid-July. Travelling by bicycle across climate zones throughout the year, you will inevetibly encounter difficult weather conditions sooner or later, so I did not worry too much about arriving in summer in Central Asia. How hard can it be, I thought? I just need to make sure I have enough water, set off riding early each morning, take it steady and sit out the hottest part of the day. No problem.

Looking back now from the comfort of a Dushanbe hostel, I am extremely glad to have the events of the last month well and truly behind me. (Actually I’m in Khorog, Tajikistan now, as I didn’t get this finished before leaving Dushanbe – sod deadlines, remember:). Here’s how it all panned out.

Scouting for cheap lodgings in Aktau I had the good fortune to bump into Alain, a French backpacker who was as dismayed as I was at the prospect of sleeping in the filthy, smelly confines of the only really budget hostel in town. We elected to share the cost of a non-shit-stained hotel room elsewhere, and I spent a couple of companionable days in that pleasant but oddly uninspiring edge-of-the-world city, gathering supplies and steeling myself to head out into the desert. Loading the bike with fourteen litres of water and food for five days, I ended up leaving Aktau around 2pm, the hottest part of the day – perhaps not the most auspicious start. Nevertheless I managed to get 120km under my wheels without incident before bedding down under the Milky Way, amongst the wild horses and camels in the scrubby sands just west of Shetpe.

Up and away by 6am the next morning, I cruised through the next 110km of excellent asphalt and was starting to wonder what all the fuss was about. Sure it was getting hot, but at this rate I’d be in Beyneu for a slap up feed on my birthday the following day.

The blacktop ran out at noon and at that point, propelled by the momentum of the morning and buoyed by the prospect of a celebratory beer the following night, I made my first serious error of judgement. Rather than stopping and seeking shelter in the rag tag collection of shacks scattered near the end of the tarmac, I tore into the rough road, thinking that some other roadside shelter was bound to appear before the sun became too strong to ride any more, and I had another hour or so before then. From here on the ‘road’ was a diabolical dirt track, basically sand and gravel with embedded rocks and pebbles. Every few minutes, heavy trucks squeezed past each other, releasing dust clouds that engulfed everything in their wake, and their tyres had long since turned the rock free parts of the road into a corrugated washboard.

Thirty metres to the right of this ‘Bicycle Demolition Derby’ (as it is known in touring circles) a new road is under construction. The pristine asphalt is a joy to ride, but only for a kilometre at a time between the yet to be built bridges over deep cuttings perpendicular to the road (I suppose they are for animals to pass under the road as I can’t imagine so many culverts would be needed for drainage in a desert). At each cutting I found myself floundering though soft sand to get down off one section of the new road deck and up onto the next. Soon realising that it was less effort to stick with the spine-jarring old road, I pressed on and after an hour of this, with no sign of shade from the fierce sun in any shape or form, I was starting to become concerned.

The exertion of the morning had taken its toll; snack breaks could not sustain the colossal effort of riding a heavy bike through this desperate terrain and I felt ghostly shivers up my legs and arms – not a good sign when the air temperature is in the high forties Centigrade. Immediate shelter from the sun was now imperative. I scoured the distant horizon for a stationary truck to crawl under, or a road construction crew that must surely be about somewhere, but could see only sand and the occasional dust plume trailing behind juggernauts thundering through this Mad Maxian wilderness.

Finally spotting a few large sections of concrete pipe scattered between the old and new roads, I found one that offered shade from the scorching intensity of the 1.30pm sun and I crawled inside. In half an hour my pulse was back to normal and I took stock of the situation. I had about two litres of water and plenty of food, but for some reason I could hardly eat. During the next four hours I struggled to force down bread with jam and molten cheese but my appetite had deserted me. By 5.30pm the infernal solar death ray had arced across the sky and was now seeking me out at a lower angle, forcing me from my hiding place. As I wearily bumped along the road my eyes were drawn upward as, to my horror, the perimeter hills of this enormous plane converged into a headwall in front of me, up which the road ahead climbed, apparently vertically, to the sky. My mind recoiled – surely the route to Beyneu went around the corner and sneaked through some unseen valley? No way could the lumbering trucks possibly get up such an incline, I reasoned. The bright yellow construction plant visible halfway up the dusty mountain road looked like it might topple down at any moment – this was obviously just a quarry road.

A sign announced the start of ‘the dangerous section’ and the reality dawned that I was going to have to muster the energy to get myself and my bike up this monstrous incline. The sign had the gradient as 12%, although I swear in places it was more like 20%. With the same rock-encrusted, potholed substrate as the plateau road but with an even thicker layer of fine sandy dust, this was without doubt the hardest bit of road I have ever tried to ride up, although the heat and my near exhausted state certainly contributed to that impression. In my lowest geat I made it halfway up, until I could pedal no more, reduced to pushing the bike for the first time ever. My head spinning from the effort, I managed another 200m, until finally I could push no further. Slumped over the handlebars, sweat filled my eyes and I grasped for options. I simply had to get some energy into my system but all the food I had was dry, while the water in my bottles was hotter than most people take their tea, and was incapable of quenching my raging thirst. Dropping the bike I flagged down the next car that passed and mimed drinking a bottle of water. The driver handed me an ice cold bottle of sparkling water and indicated that he wanted me to take it all, quickly driving off in case he ended up with a dead body to deal with. I collapsed in the tiny triangle of shade of provided by a mound of rubble at the roadside and proceeded to gnaw at one of the bizarre cone shaped nut and sugar confections that I had bought in Aktau. With the texture and taste of sugary chalk, it took the entire litre and a half bottle of water to get this horrid snack down. No sooner had the glucose found its way into my limbs and I managed to clamber inelegantly to my feet, than I was immediately felled by agonising cramps in my hamstrings and quadriceps (in both legs), which set me sprawling and twitching on the stony ground like a marionette with its strings cut. With tears in my eyes I massaged my spastic pins and hauled myself cautiously back to my feet and onto my bike once more. Huffing and puffing like the Little Engine that Could I toiled up the gravelly hillside until, over an hour and a half after starting the 2km climb, I crested the ridge and soon after found myself on smooth asphalt again.

By now the sun was sinking low on the horizon behind me, so I tucked down in time trial position to pedal on, still hopeful of reaching Beyneu the next day for a beer on my birthday. An empty car transporter truck stopped in front of me, the Russian driver jumped down from the cab and offered to take me to Beyneu, but instinctively I refused. I could still do this on my own, so I expressed my thanks and rode on into the dusk, determined to rack up the 175km required that day to keep alive the dream of making it to Beyneu next evening. Ten minutes later a van stopped on the opposite side of the road and the driver jogged over to ask if I wanted a lift to Beyneu. Although his vehicle was facing towards Aktau, he explained that he had just passed me and swung round to pick me up. As I weakly protested that I wanted to ride on, he voiced strong scepticism about my chances, pointing out that over 210km still seperated us from Beyneu and the road was not surfaced throughout. And then the penny finally dropped: if, in the middle of nowhere, two vehicles in ten minutes offer to save you from having to repeat the most horrible afternoon’s cycling of your entire life on your birthday, you should count your lucky stars, throw your bike in the car and make with the pleasant chit chat. I collapsed into the passenger seat, and soaked up the air conditioned comfort of not having to propel myself any more for the day. Demir, my rescuer, explained that he is an eBay entrepreneur with shops in Aktau, and was making his twice weekly 6 hour each way commute to pick up stock from his warehouse in Beyneu when he spotted me and thought I must be knackered or mad. His four wheel drive Lada floated over the potholed, stoney miles to deliver me effortlessly to Beyneu in a couple of hours, where he generously negotiated on my behalf with the owner of the station flea pit hotel (after I rejected the first place as too pricey).

And so I marked the advent of my fortieth year on this planet in a mouldering room in a wild-east frontier town, licking my wounds and seriously considering taking the train to elude a further spanking by the desert. I had been tipped off that ‘from Beyneu, things get worse’, and frankly the prospect of anything worse than the previous day’s tribulations was impossible to countenance. But the railway ticket office staff were obstructionate, denying the possibility of taking my bike on the train, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary in internet blogs by other cyclists who had passed through Beyneu. But the picture painted in the blogs I read, of a twelve hour journey in a metal box through 40 odd degree heat with no air con but plenty of unwanted attention from vodka sozzled idiots, persuaded me that the train was likely to be no soft option either. So with grim determination, I replaced my Marathon Pluses with knobbly mountain bike tyres, restocked my food and water supplies, grit my teeth, girt my loins and struck out on 1st July toward the Kazakh-Uzbek border at Karakal-Pakstan.

By mid morning the air was almost too hot to breathe and a strong, dry headwind felt like a blow torch, cooking my eyeballs behind my sunglasses. Trying to cool down, I poured water from my bottle over my head and almost scalded my scalp, and I was dry again inside two minutes. The road was another stretch of rough potholed hell, but perhaps because I had made a conscious effort not to exert myself in the heat after taking such a beating two days before, perhaps because I now had fat mountain bike tyres on the bike, I found it fairly straightforward if thirsty work. Certainly it was no worse than the Shetpe-Beyneu section.

At the border a queue of hundreds of people crowded in a caged corridor up to a gate on the Kazakh side. I suppressed rising alarm – it could take all day to get to the front of this exodus – but to my surprise the locals parted around my bike like the Red Sea before Moses and I was passed up to the gate. Armed police beckoned me inside the compound and ushered me to the front of yet more queues inside the immigration and customs buildings, calling ‘tourist!’ to the other people waiting as if I was some kind of visiting dignitary. The bureaucracy was fairly light touch on the morning I passed through, and after a half-hearted search of my panniers by a friendly guard I was on my way within two hours of rocking up.

As there are only about three ATMs in the whole of Uzbekistan, I’d planned to bring enough cash to see me through my three weeks or so in the country. Unfortunately I had been unable to obtain dollars from the ATM in Beyneu and decided on the spot that $300 worth of Kazakh tenge would have to do instead, which I had heard I could exchange at the border as easily as dollars. Right enough, in the no man’s land between Kazakh and Uzbek immigration I was discreetly propositioned to exchange money. Getting into the haggling spirit, I scoffed at the initial offering of 11 Uzbek som to the tenge, pointing out that the proper rate was 13 point something. The woman fixed me with a beady eye and came back with ’18 som the tenge’. I was a bit flummoxed by this huge error in my favour, but tried not to let on and agreed readily, converting my small wad of Kazakh bills into to a carrier-bagful of rubber banded bundles of Uzbek 1000 som notes. Cock-a-hoop at being an instant millionaire, I pedalled out into the Uzbek desert and made it in a couple of days to a cheap motel I had been tipped off about, so I could obtain my first official registration slip, which I would be required to produce on exiting the country.

I can’t remember where I first heard that Uzbekistan has an offical bank exchange rate and a black market rate (a product of 10% annual inflation and the de facto rate for virtually all monetary conversions in the country), but my arbitrage triumphalism was short lived. Whereas I thought I had driven a hard bargain for the equivalent of 3400 som to the dollar, way better than the 2250 quoted in the XE.com currency converter on my phone, the border money changer had in fact seen me coming and paid far less than the universally available black market rate of 4500 som the dollar. D’oh! As it was I didn’t do all too badly – at that border few people obtained rates much better than mine apparently, and I still had enough dollars to pay for things when dollar prices were given but black market conversions assumed. But it was an important lesson learned – in future carry more dollars as a contingency fund to avoid being stuck with stranded assets of local currency from the previous country, and exchange only a few dollars at a time until certain of the best black market rates.

The western Uzbek desert is parched cauldron of featureless scrub and whirling dust devils, a plane so vast and empty that objects appear on the horizon an hour before you reach them by bicycle. I always had the impression that I was riding slighty uphill as the road appeared to rise up to meet the distant horizon, but the ease with which I could freewheel gave the lie to the illusion. Against headwinds and in suffocating heat I ploughed on through the grindingly monotonous landscape, struggling as usual to get down enough calories, my appetite noticably diminished by the heat. In a bid to stay motivated and positive I pumped the pedals to high tempo tunes on my headphones. I can report that Death from Above 1979’s magnum opus, You’re a Woman I’m a Machine, results in gratifyingly high roadspeeds, but at the price of unsustainable and headache inducingly high pedalling cadences. Archie Bronson Outfit and the Phantom Band yield a nodding dog pedalling style with rather more slapping of the handlebars than might strictly be considered safe on a road with any real traffic, while the Kills’ Dead Road Seven could well have been written about the Beyneu-Nukus highway (go down there if you wish, indeed).

After eight days of early starts, long siestas and late finishes I was within a whisker of reaching Nukus, the first city in over 800km since Aktau, where I looked forward to a shower, some decent food and a chance to recharge my batteries. Late in the afternoon on my approach to Nukus I was feeling a touch pealy-wally after scarcely eating during the long and very hot day. By now I was living on cloyingly sweet, chemical-laden cakes, the only portable food available from the motel’s extremely basic tuck shop. I stopped at a roadside vendor of cold drinks and guzzled half a litre of ice cold Fanta. My initial ecstasy gave way to a weird gurgling deep in my guts and feeling unsteady on my feet I sat awkwardly on a tiny stool under the wicker shelter. I must have cut a pathetic figure, as the woman who sold me the pop looked concerned and asked if I was on a record attempt, then kindly asked if I wanted to lie down, and showed me to a wire-base bed outside her house at the end of the lane.

Once I went down I could not get up, and the next thirteen hours are a blur of nauseous, exhausted semi-consciousness, during which ducks quacked away beneath me, dogs barked constantly and locals drank beer in the yard around me. Some guy sat on the edge of my bed to harrangue me in Russian and Uzbek while I smiled wanly then pushed his hand away and told him not to poke me in the ribs again unless he was happy for me to throw up in his face. After dark, one of the woman’s sons brought me chai and dumplings, and out of gratitude I attempted to chew but could barely manage one. My struggle must have been witnessed as the next time I opened my eyes the bowl of meaty dumplings had gone and a plate of watermelon was on the ground in its place. At some point the rest of the family took to other beds in the yard and dozed through the night beside me, and I was dimly aware of a blanket being placed over me. At dawn my bowels woke me with an urgent alarm call to get to a toilet or behind a bush with all haste – the latter being my favoured option given the rustic character of my present billet. I made my sincerely grateful goodbyes to my Uzbek guardian angel, who was already up and about while her four sons slept (I now have a sneaking suspicion I stole her bed), accepted a generous gift of two cold bottles of water and made a dash for a stand of trees half a kilometre up the main road. I don’t know for sure what caused that first bout of travellers’ diarrhea, but I do know that after limping out of the desert into Nukus I was unutterably glad to find an air conditioned hotel room with a beautiful bathroom, and for three days I never strayed too far from its gleaming ceramic toilet.

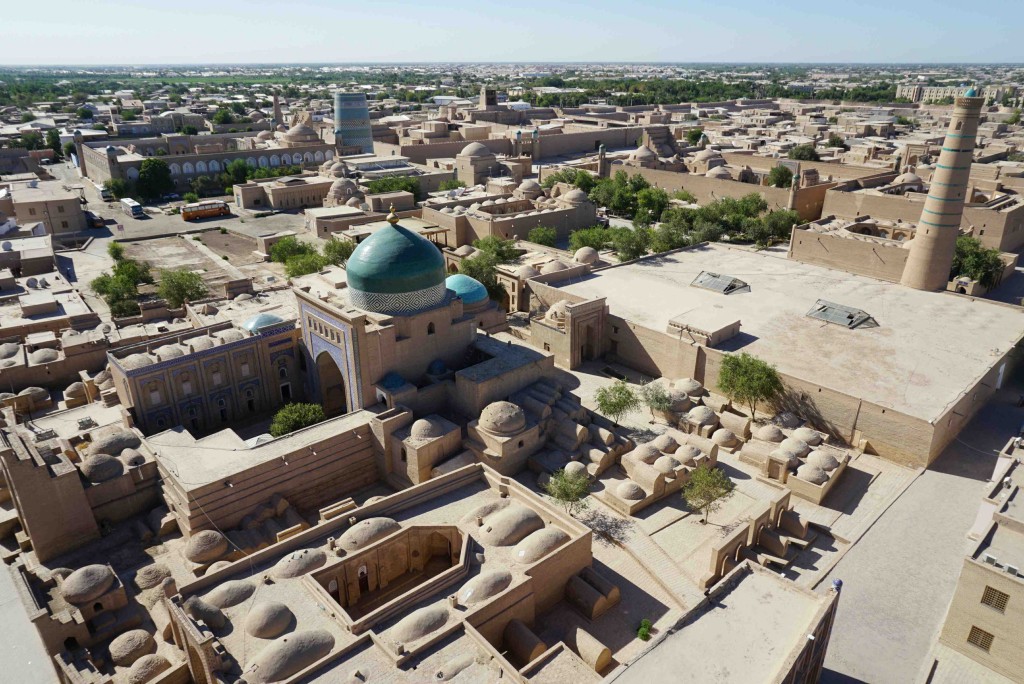

Eventually feeling strong enough to hit the road again, I made my way gingerly to Khiva, the first of the ancient Silk Road cities on my route through Uzbekistan. No sooner had I arrived in town than I bumped into Jonathan, a Swiss motorcylist I had met in the embassy in Baku, who guided me to the great hostel he was staying at (Alibek B&B). I spent a couple of pleasant days in Khiva as a camera toting tourist, chatting with other cyclists and backpackers for the first time in weeks – Jonathan was the first traveller I encountered since leaving Aktau. An eerily empty place after the tourist throngs have dispersed in the early evening, it is then that Khiva comes into its own as the city walls, mauseleums and minarets are bathed in the warm orange glow of the setting sun. Alibek B&B has the best seats in the house, its verandah directly opposite the south gate.

From Khiva my plan was to visit Bukhara and Samarkand, the two other principal Silk Road cities in Uzbekistan and I made a rip roaring start towards the first of these, putting in 184km, my longest day of the trip so far (a 200km day seeming a realistic prospect for a moment), without undue effort I thought at the time. To give some measure of my composure, I bought a bottle of beer from a house that served as village shop when I stopped for water to camp that night. My celebrations were premature, though, as within ten minutes of pitching my tent in the desert, the sands began to hum with whining, bloodsucking, airborne evil. Mosquitoes! Thousands of em. A farcical, frenzied flap to get my cooking done and into the tent without admitting any winged intruders was a dismal failure, resulting only in beer spilled over half the tent floor, sand in the cooked pasta, and me sparked out still clothed, being bitten repeatedly more or less head to toe throughout the night.

In no mood to linger after such a horrific camp, following a perfunctory breakfast of coffee, oats and water I got my first taste of real Uzbek desert – the Kyzyl Kum. Although mostly scrub and sand wilderness, in places the Kyzyl Kum is the desert of popular imagination, the sand piled up in dunes, moving and remaking itself. More significantly, it is hilly and in mid July it is at its hottest; by 11am the air temperature was in the high forties Centigrade, simply too hot to move. What wind there was acted like an oven fan, with no cooling potential whatsoever. And at this hour, in this unspeakably inhospitable place, my bowels decided to rebel once again. To my immense relief a chaikhana appeared at the roadside (only the second time I encountered one at a ‘useful time’), where I took refuge in the air conditioned back room, making frequent forays to the unholy hole of a long drop latrine, fifty metres away in the scorching desert. Wretched with the exhaustion of the previous day, torrential guts and zero appetite, I pondered my options. At 6pm the heat was still as oppressive as a sauna and I sat on a platform bed out front and watched for a suitable vehicle to hitch a ride across the 250km or so of desert to Bukhara. Nothing doing. The owner of the chaikhana had the friendly, thoughtful demeanour of an Uzbek Jim Al Khalili, and commiserated with me in surprisingly good English. He offered to ask other customers if they could take me, but added that probably I would be better to sleep in the air conditioned room and try again in the morning.

By morning I resolved that I could not wait for a lift to come to me, so before the sun was up I set off and feebly trundled along for 50km, stopping to run behind a sand dune every hour or so. The biscuits I snacked on were like sand in my mouth, and it was obvious that with a growing headache and rock bottom energy levels I was in no state to ride another baking day in the Kyzyl Kum. Watching for approaching vehicles in my handlebar mirror, I jumped off the bike at sight of a possible lift to flag it down. This was suprisingly easy to do, but for various reasons none of the first four vehicles that stopped could take me to Bukhara, although one chap in a small car stuffed to the gunnels with four passengers and their assorted luggage was adamant that he could take me, repeatedly pointing at my bike frame making a ‘stick snapping’ gesture with his fists. Since my bike would not have fit into his car had it been empty, I demurred gratefully but firmly. Eventually I snagged a light truck that was going my way and with my bike in the back, I bumped along the potholed road sandwiched between Morad, the friendly driver, and Rassoul, the gratuitously inquistive co-driver with the most penetratingly loud voice I have ever had ten centimetres from my ear. But for all his auctioneer meets town crier interrogation, constant tobacco chewing and flobbing out the window, Rassoul was a brick – insisiting on paying for my coke and water when we stopped for drinks. To my profuse thanks, the guys set me down just outside Bukhara and I turned the pedals limply and crawled into town.

Once again, my hostel hunt was beautifully simplified by bumping into a prior acquaintance as I pootled into the old town centre. This time it was Jess, an Australian backpacker turned cyclist, whom I had met briefly in Khiva, who shepherded me into a safe bolthole. At Hotel Rumi, owner’s son Bekhruz took all guests under his wing, going the extra mile to help with everything, escorting us on shopping trips, negotiating with shopkeepers, finding ATMs, arranging veggie food. Rumi was a great place to recover, chat with the many other touring cyclists and backpackers staying there, and wander round the beautiful old city of Bukhara.

After four days chilling out, loading up with Bekhruz’s mum’s superb veggie cooking and with a smart new haircut, I was raring to get going again, and looking forward to catching up with Ritzo, Henk, Jess, Alex and Nat who had all departed already for Samarkand. A killer headwind made the fairly flat 280km from Bukhara to Samarkand a surprisingly tough slog. Looking for a camping spot in the evening near Navoiy a local lad on a mountain bike (as opposed to the standard issue single speed boneshaker with swept back handlebars) cruised up beside me and chatted amiably, asking if I wanted to come to his house – his ‘hotel’ he called it. Confused but happy to see what happened, I followed Ozod along a series of increasingly dusty back lanes to his family home, where four generations fussed over me and their English teacher neighbour, Monira, called by to translate. Mercifully, the family was content to get their head down early and I was glad to follow suit; small wonder as the household was all astir by 5.30am and out to work by 6am the following day, Sunday or not.

Although never my favourite Steely Dan album, Samarkand has enchanted me since I first heard the name as youngster. Indeed, during the early days of my desert crossing campaign I had a mind to call this blog post ‘The Golden Road’, the refrain of Flecker’s famous poem going round and round in my head.

We are the Pilgrims, master; we shall go / Always a little further; it may be / Beyond the last blue mountain barred with snow / Across that angry or that glimmering sea / White on a throne or guarded in a cave / There lives a prophet who can understand / Why men were born: but surely we are brave / Who make the Golden Journey to Samarkand….

Sweet to ride forth at evening from the wells / When shadows pass gigantic on the sand / And softly through the silence beat the bells / Along the Golden Road to Samarkand…

We travel not for trafficking alone / By hotter winds our fiery hearts are fanned / For lust of knowing what should not be known / We make the Golden Journey to Samarkand

(From The Golden Journey to Samarkand by J.E.Flecker)

In reality, the road is far from golden (see above), and Samarkand itself is a bustling city, with its heritage sites thinly scattered amongst busy roads and shops. Despite the magnificence of the Registan and assorted mauseleums with their iconic blue domes and facades, Samarkand exuded little of the Silk Road charm of Khiva and Bukhara. In the event, I was content to spend a couple of days there before teaming up with clog-wearing Dutch cyclist, Ritzo, to head into the hills toward the Tajikistan border and enjoy some company on the road for the first time since Georgia.

Disaster struck on our first night camping together. I awoke to the peculiar hollow sound of wood knocking on stones at two second intervals. Emerging from my tent I found a perplexed Ritzo, clog on one foot, sock on the other, wanting desperately to know ‘have you seen my other clog?’. While I had pitched my tent against the possibility of rain during the night, Ritzo had bivvied on his sleeping mat under a tree, with his belongings piled around him and his clogs by the foot of his makeshift bed. Waking to find only one clog remaining, naturally enough his first thought and dearest hope was that I had pinched it as a joke. I had to disappoint. Thinking back I recalled that as I dozed off the previous night I had heard an animal knock over the pot containing the remains of Ritzo’s dinner, and apparently he had indeed seen off some beast and weighted down the pot lid with a stone and thought no more about it. As Ritzo’s clogs were his only footwear on this trip, we optimisitcally scoured the surrounding area, river bank and fields for the errant klompen. At moments like this, standing on a dusty farm track at 6am on a Wednesday morning in the middle of nowhere in Uzbekistan searching for a missing clog, that you start to wonder how has your life come to this?

The search proved futile, so with Ritzo now wearing my spare trainers we spun up the mountain switchbacks and worked our way steadily towards the border. Towns here were much more closely spaced than in the west of the country, where I had cycled for days without hardly seeing a soul. As always people were extremely inquisitive, shouts of ‘atkuda?’ (where are you from?) emanating from every passerby it seemed. Unseen children squawked ‘hello hello hello’ from trees and fields, sounding like troops of monkeys, the more gentle voiced ones like cuckoos. People working in fields and at roadside stalls offered us melons for free – in three weeks in Uzbekistan I ate more melon of various kinds than in the last ten years of my life. Which was just as well as the food in cafes was, by and large, pretty tough to face and even harder to digest, although repeated bouts of sickness certainly did nothing for my appetite. (I was literally gutted to fall sick again two days before the border – will this ever end??!).

At the joyous discovery of a large and incongruously well-stocked supermarket in Denau we emptied our wallets of our last few thousand som (the Uzbek eqiuvalent of coppering up), to feed ourselves for the next twenty four hours before we could cross the border. As we sat on the steps goofing around with passersby, a smart chap came out of the supermarket and in impeccable English asked us if there was anything he could help us with. I asked if there was anywhere we could change just a few dollars so we could put together a better evening meal. ‘Come with me guys’, he says, ‘I’m the manager of the shop. Help yourself to what you want, it’s on the house’. Up and down the air conditioned aisles we walked with Umid, who explained that he had lived for six years on the Edgeware Road in London. Behind us trailed a retinue of personal shoppers carrying baskets, which they loaded with dates, nuts, nutella, fish, cheese, loaves of bread, bottles of water and passed it all through the checkout to our open arms. ‘Tell people what a good place Denau is’, said Umid. And so it is.

16 May 2018 @ 18:09

Beautiful pix, really interesting and cheerful text!!! Was there 30 yr again when mosques were still in shambles but already so beautiful and charming…. thx for the lovely report

7 November 2015 @ 15:59

I’m astounded at the dangers you’ve been through and also by the incredible kindness of strangers. Your writing is so enjoyable to read although I confess I have only just finished this part of the story. It’s like the Arabian Nights – I can’t wait for the next instalment so I’m going to get another coffee and read it now! Hope you are faring better healthwise than you were in the summer. Love, Jane

29 August 2015 @ 21:27

A suitably epic blog article for an epic leg of your journey. I was really looking forward to hearing about this part of the world and wow, you didn’t disappoint! I would never normally read something so long, but I’ve said it before and l say it again – you’ve got a real flair for writing. Together with the photos, this was an incredibly engaging piece of work. I was flicking between the bog and Google maps, trying to figure out your exact route. Pretty scary though – it looked like you genuinely could have died if things has gone slightly differently

28 August 2015 @ 22:59

Wow, wow,wow! Amazingly tough going. Love your writing style. You make me feel your pain one minute and laugh the next. Read bits to the kids tonight and showed them your pictures. They were amazed by your endurance and astounded by the pictures ; a visual cultural education of wire beds outdoors, of feasts with people sitting on the table and washing rugs in the street. Liam thought awhile and said ‘Uncle Daniel must be really tired by now’. Hope the going is good and you are recovered.

18 August 2015 @ 20:09

Even more mind-boggling than last time, on so many different levels. You make us want to be there, but without the effort and the gut-rot!! You are clearly an exceptional cyclist, traveller, adventurer, writer and photographer. The people you meet put the world into true perspective, away from wars and politics. “Restores your faith in human nature” is an old phrase, but so true!

Love and best wishes

Tom and Joan

16 August 2015 @ 03:14

Nice storytelling right there. A pleasure to have met you in Bukhara. I hope everything is going well and you are enjoying your trip as much as you can. Maybe see each other one day. I’m backpacking in Chengdu and will be on the road from Kashgar in early September. Anyway, enjoy, keep on writing and have lots of fun in China. I think it’s amazing. Take care!

14 August 2015 @ 22:43

When the going gets tough, the tough get going. That was a gruelling section you went through,with sickness and exhaustion and all. I was exhausted myself just reading your account of it. Anyway,you survived. Congratulations on actually reaching your fortieth birthday.

Great that you posted so many of your photos.

Take good care of yourself.

Love

Dad

14 August 2015 @ 17:50

Another amazing blog. Worth the wait my friend xx