Farthest from home

I arrived in Queenstown with the last rays of evening light, exhausted from a long day of packing, transfers and goodbyes. Compared to balmy Sydney, there was a chill in the January air on New Zealand’s South Island, summer or not. I had visited Queenstown thirteen years before, but recalled little of the layout or features. Tourism in New Zealand has exploded since then, with a new wave of wealthy Asian tourists on top of the hordes of European backpackers and camper-vans. Queenstown is at the heart of this boom. Despite my late arrival, the town centre was in full swing, so there was no problem finding eats and sights. Tara arrived by bus the next day from her short tour in the north of the South Island. I had missed her dearly in the two weeks we had been apart. We were both in a hurry to get moving, neither of us wanting to hang around this expensive, busy resort. In little over 24 hours I had burned through $100 on accommodation and food, more than a week’s budget on the road. Next morning we took the steamboat across Lake Wakatipu to Walter Peak Farm, where a dirt road led through a pass to the Mavora Lakes.

It was an immediate relief to leave behind the crowds and money extraction apparatus of Queenstown. We rode through pasture and open country. Stopping for a picnic, it was comforting to immediately click back into our familiar routine together – Tara constructing sandwiches while I arranged the stove and brewed up. At Mavora Lakes we realised that camping in New Zealand was going to require more thought than in Australia. Department of Conservation signs indicated where camping was allowed and where to leave fees for pitching. But we neither needed nor wanted anything the DoC sites provided, which catered primarily for motorised camper-vans. We scouted around and found a hidden beach way down off the forest track by passing the bikes and bags down a steep slope.

My first night under canvas in NZ meant my first encounter with the wretched sandflies (blackflies), which plague most of the country during summer. Like mosquitoes they swarm at dawn and dusk, but their bites caused swelling and itching that lasted for weeks. Keeping them out of the tent was nigh on impossible. Their sole merit was that they were extremely poor at evading execution. With ten minutes concerted effort we could usually squish the fifty or so sandflies that had entered the tent with us.

Entering Manipouri, signs warned about stiff penalties for ‘freedom camping’ (parking your camper or placing a tent outside official campsites). It was obvious that camper-vans were New Zealand’s current folk-devils, and we were not exempt from the suspicion or control directed at them. Trying to camp undetected at popular tourist spots was a waste of time, so we retreated a couple of kilometres to an overgrown green lane that I had reconnoitred on the way in. In the morning my ambitious plan to get the bikes over Percy Pass to Doubtful Sound (New Zealand’s deepest fjord) was trebly scuppered by the steep price of the boat cruise to the roadhead, a dismal weather forecast and the onset of a heavy cold for me. Everything militated against such a fool’s errand, so we steered towards the southern tip of the South Island. It was undoubtedly the sensible decision, but crying off an adventurous plan always leaves a stale taste in my mouth for a while.

Near Riverton we had our first brush with aggressive local drivers, who honked and swore at us to get off the road. In Australia it had happened two or three times, a relatively rare experience in three months. Of course I have years of experience of this kind of ‘us and them’ belligerence from cycling in the UK, but Tara was shocked by the open hostility (Canadians are universally and unrelentingly nice). We bailed off the main drag into a network of dirt roads through arable land west of Invercargill. The forecast storm had been slow in arriving, but it was now visibly bearing down on us. A kilometre back, the sky blackened and emitted a roar of wind that lashed us with dust and sand. A friendly farmer pulled over to say hello while we were eyeing a side lane for potential camping spots. With the wall of rain moving towards us, we asked if he thought this would be okay. No worries, just open the gate to the paddock and let yourself in, he told us. Reassured and heartened by the friendly reception, we were about to take up his offer when I spotted a better position on the edge of a clear cut area of forest, using the enormous upturned root balls of a few trees as shelter from the wind.

Next morning we warmed our bones in a cafe in Invercargill while I nursed my pounding head, and for the second time in two days decided to abandon a planned route extension. The idea of tagging the southern tip of the island at Bluff seemed strangely unappealing and pointless with 80kmh cross winds bearing down on us. In any case, the mainland actually had more southerly extremities on the Catlins coast, where we were heading next. New Zealand has a few points precisely antipodal to mainland Europe. At latitude 46 degrees south, I was about as far from home as I could get on this trip. I had made it to the other side of the world! Notwithstanding that my planned route ahead oscillated wildly between southern and northern hemispheres, probably crossing the equator another three times, in a manner of speaking every pedal stroke from here carried me closer to home.

The Catlins hills were a gem of the South Island: quiet country roads and pleasant, unshowy scenery. In Australia it would have been given a grandiose title like Catlins Great Coastal Fantasia, but in NZ they don’t make so much fuss. Hector’s dolphins patrolled Curio Bay while we wringed out our soggy clothes (by this point my waterproofs were anything but). We noticed that whenever we returned to ‘civilisation’ after a period on backroads, the reception from business owners was often rather chilly. Asking for tap water at a swanky campsite near Papatowai we were told, despite this being one of the wettest places on earth, that it was a dollar a litre. We demurred and filled our water bags for free at an outward bound centre down the road. Past the former gold rush town of Kaitangata we made camp on a headland looking back over the Catlins. The farmer drove by in the morning on his quad bike and gave us a wave. The stories we’d read complaining that it was impossible to wild camp in New Zealand were turning out to be bunk. For sure there was a weird vibe in some communities where camper-vans had made their presence felt too much, but once off the beaten track the reception by locals outside the hospitality industry was as straightforward and friendly as anywhere.

We skinny-dipped on a vast white sand beach as a rainstorm chased us along the coast, an early precursor of the approaching ‘bomb low’ weather system we had been alerted to. Gale force winds and torrential rain were due in the next couple of days, so we had been lucky to find a last minute Warmshowers host in Dunedin. Anna and her parents took every care to make us welcome, sharing meals and stories for three days while wind, hail and rain battered the coast. We caught up on repair jobs and planned our way over to the West Coast.

Unfortunately, the South Pacific conveyor hadn’t finished throwing depressions our way. We had planned a route over the Old Dunstan Road, a remote, rutted and potentially muddy track that crossed an exposed upland wilderness at over 1000m. Being caught out up there for two days in driving snow and sleet seemed didn’t sound like any kind of fun. For the third time in a week, we changed our plans and took the bail out option; in this case, the ride of shame along a ‘rail trail’ cycle path from Middlemarch.

From Omakau we picked up the Thomson Gorge Road, a little used cut-through to Wanaka. The steep climb to over 900m on rutted clay engaged every last drop of bike handling skill and endurance – the perfect antidote to the tedium of riding the groomed, flat rail trail. The views evoked happy memories of days spent cross-country mountain biking back home in Lancashire and Derbyshire.

We dug deep into our energy reserves and sought out Liz in Hawea Flat. Liz had found Tara’s Facebook blog about her trip and invited us to stay if we passed through her neck of the woods. As we were going that way, it seemed rude not to take up this incredibly kind offer. And boy are we glad we did. Liz and her family were fantastically generous hosts. Instantly making us feel welcome in her idyllic woodland retreat, Liz gave over her own beautiful bedroom and bathroom to us while she spent the summer nights in a teepee on the lawn. One night slid into three as we waited out yet more rain.

Meeting Liz, who had reached out over the internet to offer genuine human warmth made me rethink my relationship to sharing stories about my travels. I will admit to mixed feelings about sharing publicly what is essentially a very personal journey. It won’t have escaped the attention of regular readers that my dispatches have become more sporadic as my trip goes on. Partly this is because some experiences take time to process, and finding time and headspace to sit and write can be difficult when I’m on the move. But I also have an ambivalent relationship with the public persona that a travel blog creates. As an introvert, being the ‘centre of attention’ does not come naturally. To share tales from the road, I tend to channel my ‘inner extravert’ (yes, it is a nice oxymoron). But while a gung-ho, devil-may-care attitude can make for fun stories, it rings false in my own ears. On a semi-regular basis, I recoil from this superficiality and swear off inauthentic modes of expression. Unfortunately, without a working alternative at hand, this sometimes means no writing at all – the worst of both worlds.

But to meet someone who had read my words and been touched by them in some way – that was a revelation. I had always thought I wrote principally for myself, friends and family and did not actively seek a wider audience beyond that. But here was evidence that sharing builds bridges between strangers. It was also a vindication of the considerable effort that goes into recreating my life on the page. Not for the reward of a cold beer and a comfy bed – hostels and of course the wonderful network of reciprocity-based hospitality called Warmshowers can supply those comforts. But to present a sufficiently approachable and interesting character, such that a perfect stranger would feel inspired and empowered to initiate contact out of the blue – that was heart-warming in a different way. I resolved there and then to stop being such a curmudgeon about sharing and make it a priority to develop my outreach activities.

Reluctantly dragging ourselves from the sanctuary of Liz’s sylvan home, we slipped over the Haast Pass in atmospheric rain and mist. Rainbows bestrode the valley as we swept to the coast at dusk. The West Coast road is a major artery on the camper-van circuit. NZ’s recent poor cycling safety record was on our minds – there had been several recent fatalities of touring cyclists. We were on high alert on this section, but in the event there wasn’t nearly as much traffic as anticipated and tourists were generally well-behaved. Occasionally a truck might catch us unawares and pass too close when we were unable to ride in the primary position out from the edge of the road, but by and large it was hassle-free riding. The odd thing was that, as a popular cycle holiday destination, New Zealand attracted a different set of cyclists than we’d been used to meeting in other countries. When we met other loaded touring cyclists in NZ our enthusiastic greetings were usually met with awkwardness; often cyclists didn’t even pull over for a chat. Here we were indistinguishable from the hundreds of other bicycle tourists scattered around NZ on holidays, many of whom didn’t see the need to befriend a couple of weirdos like us.

The West Coast is renowned for orographic rain – moist ocean air is forced up and over the Southern Alps, dumping rain on the coastal road. We followed the band of lush coastal vegetation for three days, periodically getting soaked then drying out next day.

North of Franz Josef Glacier we’d endured a tedious cold, wet day’s riding and were on the limit of energy when we set up camp. In our haste to get dry and warm we failed to notice a fault with the fitting of the fuel pump to my MSR fuel bottle. Pressurised gasoline leaked and caught the flames at the burner. It was a close call. Had we been performing the operation in the porch of the tent as per my usual wet weather drill, we would have been in serious trouble. The ensuing fireball would probably have taken the tent with it. As it was, we were able to get the fire under control quickly, but not before it had done some damage to my fuel pump. Luckily I had the necessary replacement parts with me. This kind of almost-disastrous incident comes as a hard slap in the face when it happens at an already emotional time when you’re tired. It is a reminder that although we can perform our camp routines blindfold and one-handed, it is imperative to always pay attention. The same goes for cycling itself. Simply by virtue of exposure, we incur a greater risk of accident on the roads than virtually everyone else. Doing what we do, we simply spend more time in the danger zone.

Cold, wet, hungry and with a now suspect stove (Tara’s Whisperlite had already been sent away for repair after the fuel control valve thread became stripped), we rallied to get a handle on the situation. Once installed in the tent with hot food and dry clothes, it was easier to make sense of events. We arranged to stay with a Warmshowers host a couple of days north to dry out and regroup before heading over Arthur’s Pass to Christchurch.

We arrived at Kevin’s place in Hokitika ahead of yet another heavy downpour. Kevin’s urbane conversation and dry wit was just the tonic to pass an evening and morning. Out of Hokitika we followed a section of the West Coast Wilderness Trail. The effort of muscling our overweight bikes up and down the steep man-made trail was more than compensated by the Jurassic Park feel of the place. Dew drops on gigantic, prehistoric tree ferns glinted in the afternoon sunlight. The air hummed with bird and insect life.

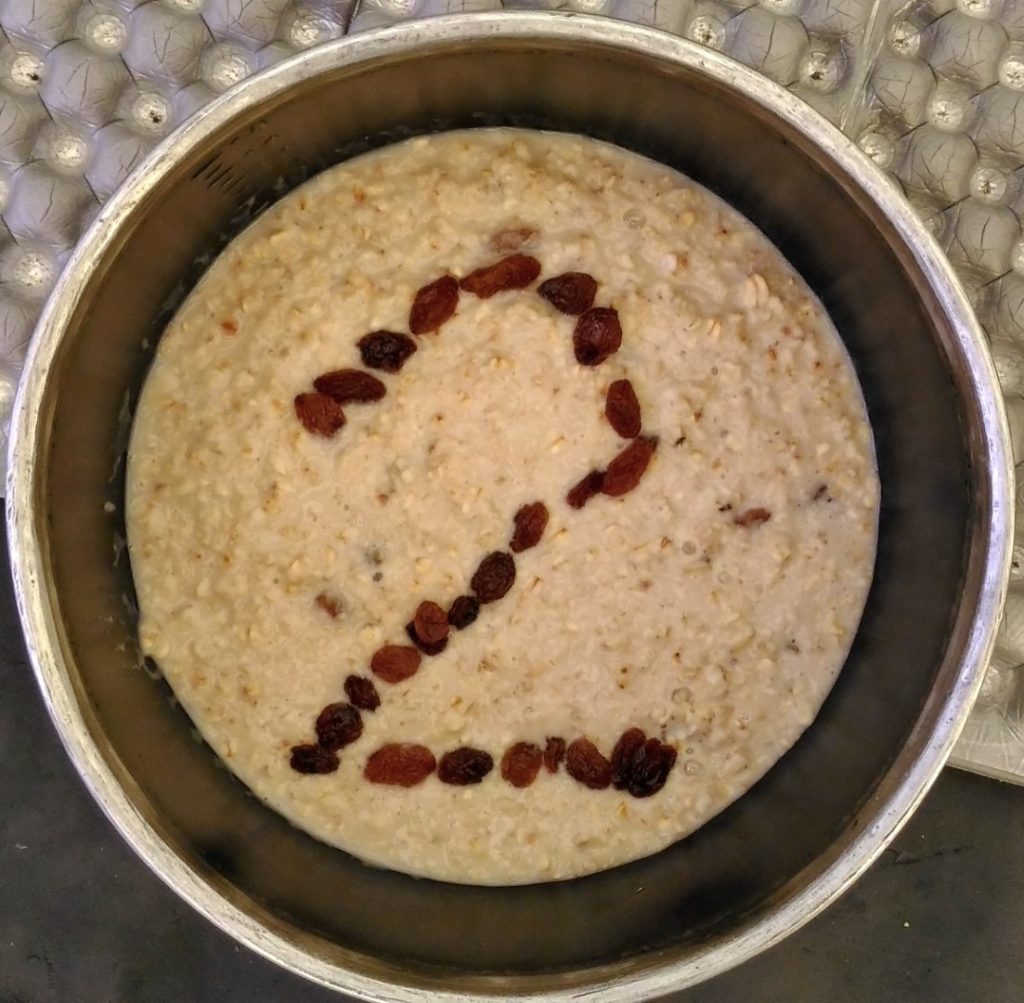

We were both in peak condition by now. Despite a few sections approaching 20% gradient, Arthur’s Pass fell under our wheels with no dramas. (We were also aware that a French cycling family we’d bumped into a couple of times was coming up a day or two behind us on a tandem with a heavily loaded trailer. If they could get over this hill, which they certainly would in their own inexorable style, then we should have no trouble). In the quiet of evening, the road beyond the pass gave superb riding. Gin-clear rivers sploshed and gurgled over pale cobblestones, transcribing broad valleys that cleft the enormous mountain vista. Our last night camping together before Christchurch was textbook perfect: a hidden side valley, beside a mountain stream with pools deep enough for a bath and views of the nearby peaks. But for the blackflies, that spot would have rated 10 out of 10.

We pushed hard to get to Christchurch while the wind pushed back equally hard in the opposite direction. It seemed to anticipate our every turn, veering and backing to compensate for every course correction. In Diamond Harbour we were treated to five star hospitality by my old mucker, Mark, flatmate from my pre-university days, more than half a lifetime ago, and his wife Gillian.

The joy of reaching this homely house was offset by the sadness of parting ways with Tara. In a few days she was due to start a summer job back in Australia to replenish her travel funds. Goodbyes are never easy and this was probably the toughest of my life. We had been through so much together in the last six months. Except for a couple of weeks over Christmas and New Year, we had been constant companions. We had come through the deserts of Australia with a deep appreciation of each other’s qualities. We knew we would miss each other badly. We planned to reunite in Japan in a few months and talked about how to achieve a balance between companionship and time alone. Being in constant company – living in each other’s pockets, sharing every activity – had sometimes felt stifling. I found myself craving solitude. To recharge. To write. To think.

Sure enough, with more headspace at Mark and Gill’s, I managed to make a dent in my writing backlog. Two weeks slipped by, then it was high time to move north and visit friends in Nelson. I pedalled out of Christchurch alone for the first time in over six months. Although strangely disorientating at first, I soon settled back into my familiar routines. Camping was once again a wordless enterprise. And while I missed Tara acutely, I also savoured the tranquillity. I am reminded of John Steinbeck’s note to himself in Travels With Charley, “‘Relationship time to Aloneness’… Having a companion fixes you in time and that the present, but when the quality of alone-ness settles down, past, present, and future all flow together. A memory, a present event, and a forecast all equally present.”

I charged harder than was sensible for my health. I finished each day physically wiped out, but content to be doing what I loved, what I was good at – testing myself physically and mentally out in the wild, keeping my own company, being self-reliant. Challenging gradients out of Hanmer Springs led to the celebrated Rainbow Road. Built as a service road for the overhead electricity conductors across the vast Molesworth and Rainbow Stations, the route has a real wilderness feel reminiscent of the Scottish Highlands. Tara had ridden there in the opposite direction two months before, when I was in Sydney for New Year. My thoughts often went back to how she must have enjoyed this or that vista, or how she must have had to dig deep to get through a particularly rough and loose section of the track.

By the time I rolled off the dirt back onto asphalt I was buzzing with enthusiasm for solo touring again, having shaved a whole day off my five day ETA to Nelson. There, I had a long-awaited reunion with Dave and Jane, dear friends from my Aberdeen university days. Arriving at dusk, I soaked up the sunset over the Marlborough Sound, and indulged in local brews and fond reminiscences. I had visited Dave and Jane thirteen years ago when they first moved to New Zealand (one of only two countries outside Europe that I had visited before this trip). The long absence was no barrier to reconnecting. I felt more at home there than anywhere else since leaving Britain two years before. A five or six day furlough slipped to two weeks, as I overhauled the website and made further inroads into my writing backlog. My intention had been to tour the North Island extensively. But in the event, the pull of friendship and hospitality in Christchurch with Mark and Gill and then in Nelson with Dave and Jane and family proved stronger than the prospect of a wild goose chase north of Auckland.

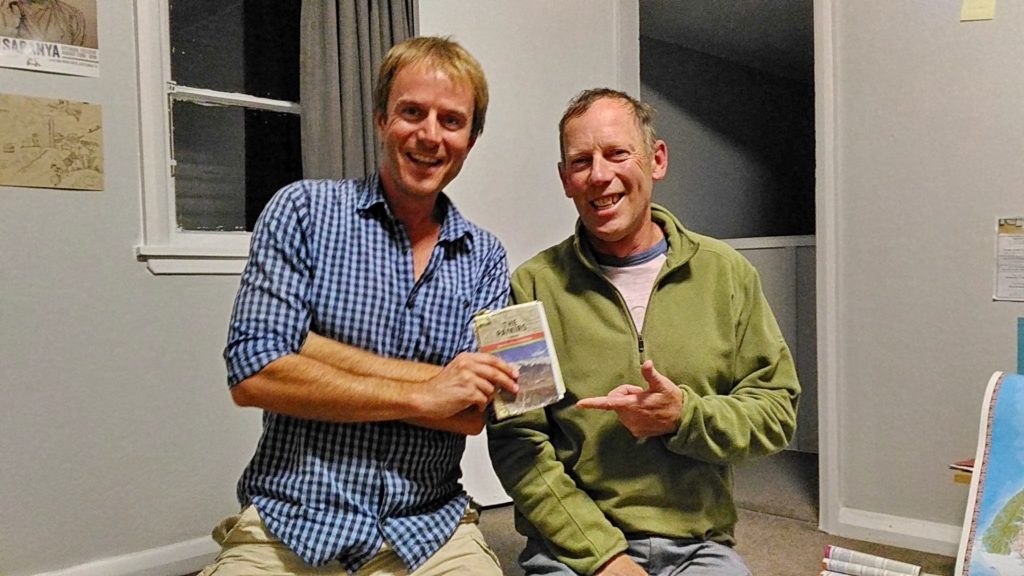

I left Nelson on a rainy afternoon with ten days to get to Auckland for my pre-booked flight to South Korea. In Wellington I was welcomed by Patrick and Dolores, Warmshowers hosts for whom I had a special delivery. Eighteen months earlier, at a hostel in Kyrgyzstan (where she and I first crossed paths, incidentally), Tara had picked up a used map of the Pamir Mountains. She had kept the map in her pannier ever since, thinking that one day she might be be able to return it to its original owner, whose name and New Zealand home address was on the cover. I had teased her about carrying sentimental ballast for thousands of miles. But now she had entrusted the map to my custody for the last leg of its homeward journey. Patrick was stunned when I presented him the map, which sparked a pleasant evening revisiting our mutual Silk Road cycle trips.

Out of Wellington, I was glad to escape the dreary main roads onto back roads whenever possible, adding distance and time, but reducing the dangers of the busy North Island road network. Patrick had generously arranged for friends of his to host me in Whanganui. Ian and June took wonderful care of me, treating me to the hospitality their own son had enjoyed on international bike tours. I followed the Whanganui River to Ratihi. I had been warned that this back country was ‘rough as guts’, and that I should keep my wits about me in the rural settlements. It was hard to believe, but later while I chatted at the roadside with two other touring cyclists a police car stopped and asked us to be on the lookout for a person and their vehicle, missing for weeks now. “Cyclists see things that car drivers don’t”, said the perceptive rozzer. For the rest of that day I scanned the deep gorges below the road with morbid interest.

I relished every opportunity to test myself against the landscape. The river road was deceptively hilly. With only a couple of hours daylight when I arrived at the end near Pipiriki, I considered calling it a day and finding a place to camp. From there the road climbed steadily to Ratihi. But it was a beautiful evening, and I decided I’d rather ride up this Lost World mountainside in the golden light than sit and swat mosquitoes. My ambition and effort were rewarded when I crested the pass at dusk. My mouth fell open at the unexpected, arresting view of the huge volcanic cone of Mount Ruapehu, which glowed pink and purple in the fading daylight. Moments like this make me giddy. The imminent loss of daylight always quickens my senses. To witness a spectacle of such beauty, so emblematic of this region, without any build-up or expectation, is for me what touring is all about. Or at least the sightseeing part of touring.

I quickly threw on extra layers and scooted down the valley, scoping out fields and dells for somewhere to draw water and pitch the tent. At the next friendly-looking farm I couldn’t find anyone at home, so helped myself from the outside tap. As I was leaving, the young farmer appeared and offered me the sheep field adjacent to the farm or the horse paddock back up the lane, as I preferred. As always in rural New Zealand, locals were as helpful and friendly as anywhere. True, it was not always easy to locate a landowner, but whenever I asked for permission to camp it was always granted, usually with extras.

After Ratihi I had to rejoin the main road north until Taumarunui. From there my ambition dared me to throw in a side excursion on the Timber Trail mountain bike route: steep forest trails intended for unloaded mountain biking. Several other tourers had recommend it, so I knew it was doable. But in a day and a half? I recalibrated my schedule to make sure I could still catch my flight from Auckland and committed to the challenge. I made decent progress on the first afternoon, but at dusk I noticed that my blue check Columbia shirt was missing. I recalled tucking it under the strap of my rear pannier on a particularly sweaty climb around 6km back up the trail (note to self: only tuck clothes under the front pannier straps, where you can see them). Not willing to sacrifice my favourite garment to the beasts of the forest, I headed back up the steep trail, knowing that I’d have to return to the same point to camp for want of flat ground anywhere in between. The second day was even more strenuous. Nearly all the weekend mountain-biking parties were going the opposite direction, down the trail as I ascended. I sang and hollered my way up to the top of the mountain, then fought hard against the ‘bonk’ as I descended.

Two long but uneventful days ride got me to Auckland, via a very welcome overnight with Warmshowers host and fellow Silk Road veteran Stephen in Ngaruawahia. In Auckland, genial hosts Don and Sally smoothed the stressful process of packing and transporting the bike to the airport. Don, the legend, even cycled out to guide me into the city for the last two hours of my ride in New Zealand.

For all that I had heard about mass tourism making cycle touring difficult in New Zealand, I scarcely experienced the problems described by other visitors – rumours that had dimmed my eagerness to tour there. Sure, wildcamping required a little more ingenuity and consultation, but I managed it twenty-seven times, including some of the most picturesque spots of my trip. For all its scenic splendour – perhaps because of it – touring in New Zealand felt like a holiday. The adventurousness was tamed in part by a common language and well-provisioned tourist circuit. No bad thing, of course. It can’t all be living on your wits in deserts and high mountains.

My tour of continent number three – the only one on my route entirely south of the equator – was at an end. My next stop would be South Korea. There, I intended to make a quick ten day spin before taking the boat to Japan for a longer visit, until the weather warmed up enough in Alaska to begin my journey down the Americas. I was ready for something different, a change of scene and a change of culture. But as the saying goes, you should be careful what you wish for. In South Korea I got more of a change than I bargained for.

To be continued…

27 October 2018 @ 01:16

What a shame I haven’t kept up with your travels. I missed hosting you in Dunedin! Great to hear about your travels. Great writing!

4 November 2018 @ 18:57

Thanks Maureen, glad to hear you found my website. We switched ends there didn’t we, I was in Dunedin while you were in Manchester!

3 August 2018 @ 23:01

Love it as usual xxx

3 August 2018 @ 03:23

Another great read as always Dan.

You may be interested to know that I have finally started touring! I’ve been in SEAsia now for 5 months and at present I’m in wonderful, and wet, Laos, heading down to Cambodia and into Vietnam- all going well. Of course, this is all inspired via reading about other people’s blogs/posts.

Enjoy Alaska-South and thank you for the kind words. Kia Kaha- stay strong

Liz ♀️

3 August 2018 @ 03:43

Great to hear from you Liz! Now you are living the dream too!! I loved South East Asia – and Laos best of all.

So far, so good in Alaska – although I seem to have got temporarily stuck again in Fairbanks 🙂

I realised after talking to you that a ‘big trip’ is about more than just the traveller. Many folk don’t have the chance to do this kind of thing, so I feel it’s important to share some of my experiences and insights, such as they are.

All the best, Dan